by Sahiyo

On November 20, 2018, United States District Judge Bernard Friedman ruled that the US Federal Law banning Female Genital Cutting (FGC, also known as Female Genital Mutilation or FGM) is unconstitutional. With this ruling, the judge dismissed key charges of FGM against two Michigan doctors and six other people accused of practicing genital cutting on several minor girls.

However, in the same ruling, Judge Friedman acknowledged that the practice of cutting a female’s genitalia is “despicable”.

The ruling came as a shock to survivors of FGC and human rights activists advocating to end FGC, not just in the USA but all over the world. But there is more to this complex and controversial court ruling than the news headlines suggest. In order to better understand the ruling and its implications for communities that practice FGC, read Sahiyo’s comprehensive explainer below:

What is the US District Judge’s ruling on Female Genital Cutting all about?

In April 2017, the US federal government prosecuted Dr. Jumana Nagarwala, Dr. Fakhruddin Attar and his wife Farida Attar — all members of Michigan’s Farmington Hills Dawoodi Bohra mosque — for subjecting two minor girls from Minnesota to FGC. Subsequently, five other women from the Dawoodi Bohra community were prosecuted for performing FGC on at least nine girls in the Michigan area. This historic case was the first time that anyone had been charged under the US federal law prohibiting FGC — a law that had been introduced by the federal government back in 1996.

To understand the US District Court’s ruling in this case on November 20, it is important to understand the federal nature of the US government and its criminal justice system. Under federalism, some laws can be passed by Congress — the federal or central government — and are applicable to all states in the country. Some other laws can only come under the jurisdiction of individual state governments, and cannot apply to the whole country.

In his ruling in the FGC case, Judge Friedman of the federal-level district court stated that “as despicable as this practice may be”, FGC is technically a “local criminal activity”, and Congress (the federal government) does not have jurisdictional authority to regulate it. Even though the federal law against FGC has been in place since 1996, he stated that it is “unconstitutional.”

Why is this ruling controversial?

The district judge states that the crime of FGC should be regulated by individual states. But the US does not actually have laws against FGC in every single state. At the moment, only 27 out of 50 US states have a state law banning FGC. There is currently a state law in Michigan banning FGC, but the law only came into effect in 2017 after the federal case involving Dr Nagarwala and Dr Attar came to light. The doctors cannot be prosecuted retrospectively under this state law.

Judge Friedman’s ruling declares the federal law against FGC to be unconstitutional based on a technicality. However, the ruling is controversial on at least two fronts.

First, prosecutors and other human rights advocates argue that FGC cannot be considered just a local criminal activity, because it often involves transporting minors across state borders to get their genitals cut by doctors who are paid to perform the ritual. In this case, for instance, two minor girls were transported from Minnesota to Michigan to get FGC done by Dr Nagarwala. Therefore, the federal law banning FGC — which Congress had passed in 1996 under the “Commerce Clause” — should be applicable in this case. Judge Friedman’s ruling does not consider this aspect.

Second, this ruling is insensitive to survivors of FGC and sends out a dangerous message to women from FGC-practicing communities: that their lives and bodies can be put at risk on the grounds of questionable technicalities.

Does this ruling put more girls at risk of being cut?

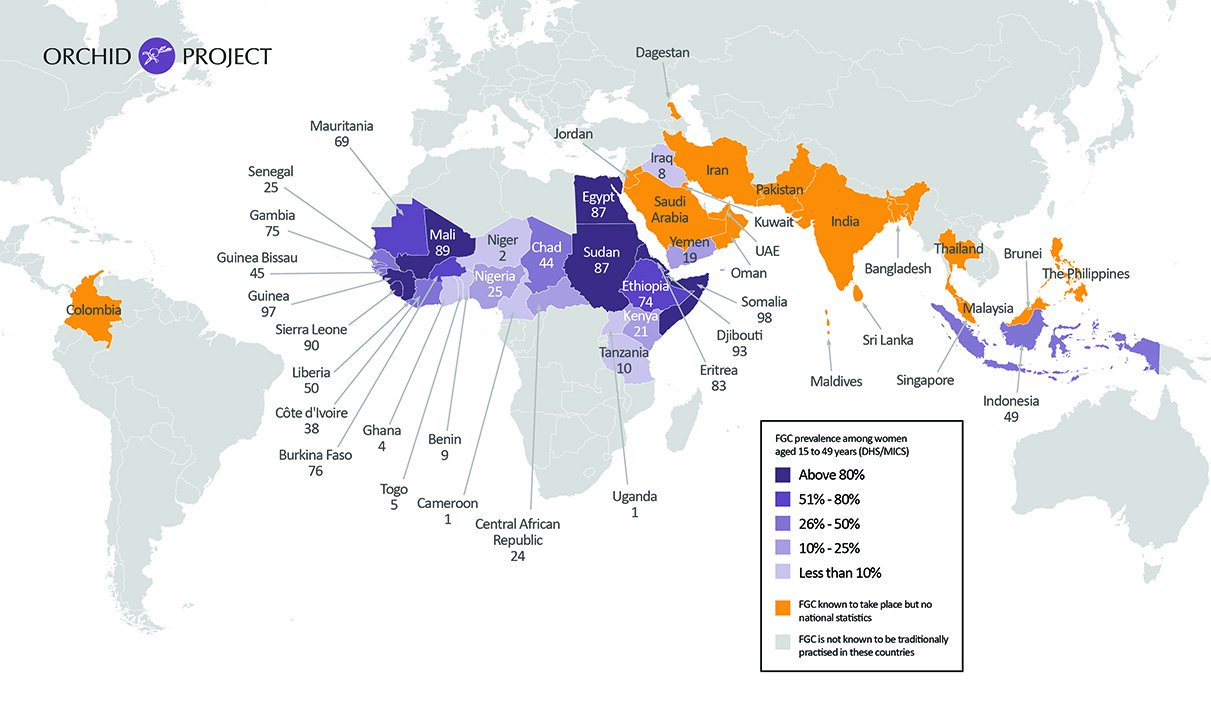

For the time being, yes: this ruling can put girls at risk of being but. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has estimated that 513,000 women and girls have experienced or are at risk of FGC in the United States. And this figure is an underestimation. Many women and girls at risk live in one of the 23 States which have not passed laws against FGC.

Since the ruling puts the onus of regulating FGC only to individual states, many of these girls are at risk of being transported from states that have laws banning FGC to states that currently do not have laws banning FGC, so that they can be cut with impunity. Only 11 of the 27 States with anti-FGC laws have specific provisions banning the transportation of a child out of the State to perform FGC.

Since the US is a strong country with a high degree of influence on global cultures, this ruling also ends up unintentionally condoning genital cutting for FGC-practicing communities all over the world. We are already seeing this in the global Dawoodi Bohra community, where supporters of Female Genital Cutting have taken to social media to celebrate their “victory” in the US FGC case, and to claim that they will continue cutting girls.

Is this the end of the case, or can the ruling be appealed?

This District Court ruling is not the end of the case. This is a lower court decision which can and almost certainly will be appealed by prosecutors from the US Government, and it is possible that over time, this case will be taken to the Supreme Court.

Additionally, two charges remain against Dr Nagarwala, including conspiracy to travel with intent to engage in illicit sexual conduct, and obstruction of justice. Her trial is set to begin in April 2019.

What is the way forward now, for those of us working to end FGC?

Laws are an important deterrent against FGC, and help to reinforce the fact that cutting female genitals is a human rights violation. In light of Judge Friedman’s ruling, activists and communities in the United States should now urge their elected representatives to pass laws banning FGC in every single state of the country. As a global leader in human rights, the US should also do this to set a precedent in many Asian countries where there are currently no laws against FGC.

However, at Sahiyo, we believe that laws can be effective only when accompanied by social change movements on the ground. We therefore encourage everyone to engage in dialogue around FGC, to break the silence around this taboo topic, listen to women’s voices and recognise that FGC is harmful to girls and women.

To learn about the history of the Michigan case, click here

Read more at U.S. Court’s dismissal of FGM/C charge in Michigan case is disappointing but does not condone genital cutting.

Read the Amicus Brief for Dr. Nargawala hearing on November 6, 2018, submitted by Equality Now, WeSpeakOut, Sahiyo, And Safe Hands For Girls in support of the United States.

Read the U.S. End FGM/C Network Statement on Judge’s Decision in Michigan Case.

Maryah Haidery talking at the Washington DC screening.

Maryah Haidery talking at the Washington DC screening.

![DOgkHoYWsAAwp8a[1]](/images/description/dogkhoywsaawp8a11.jpg)