by Ashraf Engineer

Age: 41

Country: India

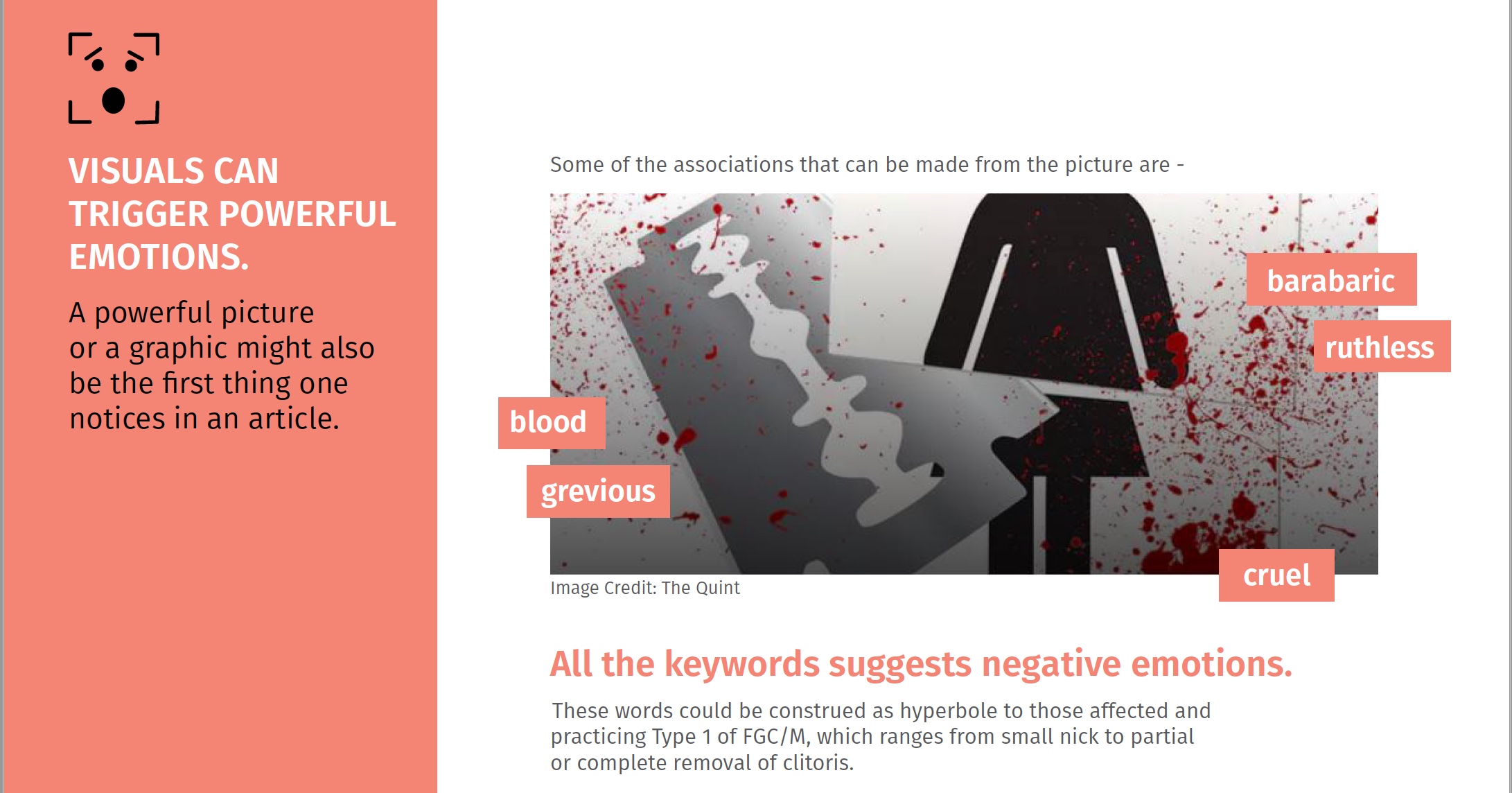

Picture this if you can without your heart racing and eyes welling up. A girl, let’s say she’s seven years old, is dressed up by her mother and told she’s being taken for a walk and an ice cream. She clings to her mother’s arm in glee and follows her, secure and happy. She is led to a house in the neighborhood where her mother undresses her and holds her down. A strange woman removes a razor blade and in a single, heart-stopping motion cuts the child’s clitoral hood.

The pain will ebb, the flowing blood will stanch but the scars will remain for life. A child has been damaged and her trust broken.

I hail from the Dawoodi Bohra community where female genital cutting (FGC) is prevalent but the thought ofsubjecting my little girl to it never once entered my mind. She is the joy of my life, she gives it meaning. There was no wayI could do that to her. Among the many ugly manifestations of patriarchy, I believe FGC is perhaps the most horrific. We see everywhere how society feels the need to control every aspect of a woman's life - from whether she can live aftershe is born and whether she can get an education to whom she can marry and when. This attitude often extends to controlling her sexuality – through FGC.

I hail from the Dawoodi Bohra community where female genital cutting (FGC) is prevalent but the thought ofsubjecting my little girl to it never once entered my mind. She is the joy of my life, she gives it meaning. There was no wayI could do that to her. Among the many ugly manifestations of patriarchy, I believe FGC is perhaps the most horrific. We see everywhere how society feels the need to control every aspect of a woman's life - from whether she can live aftershe is born and whether she can get an education to whom she can marry and when. This attitude often extends to controlling her sexuality – through FGC.

FGC is one of the most serious human rights issues before us today. It is an ongoing practice rarely talked about even by those who have undergone it, and it is not part of the public consciousness. Like marital rape and abuse, it exists around us but is rarely thought about.

According to UNICEF data, there are at least 200 million girls and women across 30 countries who have been cut. If they were to form a country, it would be the sixth most populous in the world. We are looking at an alarming crime against humanity that needs our urgent attention.

FGC is illegal in many countries – a United Nations resolution against it was signed by 194 countries in 2012 – but its abandonment will require more than a law.

Since the root of the problem is patriarchy, a social system in which males are all-powerful and wield great authority over women, men must become an integral part of the solution. FGC is perpetrated on women, but I believe it’s done to satisfy the male craving for control of female sexuality. Indeed, societies in which FGC is practiced tend to be dominated by men.

It’s time for men to speak out against this harmful practice. It’s their duty, and their collective voice will matter. If they wish to, they can make a difference. Men need to stand up and be counted – primarily as fathers of girls in danger.

This will help men too. Secure, happier women are necessary for stronger, fulfilling relationships and a progressive society.

Here are a few steps that can be taken immediately by individuals and governments:

- Pass a law that criminalizes FGC in India. The movement against this practice is gaining momentum and it’s time for the government to act.

- Start a nationwide awareness and education initiative – targeting men especially – that underscores FGC’s psychological impact as well as the danger to societal health.

- Make awareness about FGC a part of sex education in schools.

As the father of a young girl, even the thought of FGC creates a hollow feeling in the pit of my stomach. That such cruelty can be wreaked on anyone, let alone a child that has no clue of what is happening to her, breaks my heart.

As a father, your primary instinct is to protect your daughter and help her grow. You can’t do that by mutilating her body and shattering her trust.

(Ashraf Engineer, a former journalist, is a communication and marketing consultant. He recently released his first book, a Kindle-only release titled Bricks of Blood.)

(Note from Sahiyo: As an individual, another immediate step you can take to help bring an end to FGC is to sign this petition by Sahiyo and 31 international organizations. Click here.)