In my sophomore year of college, I decided to conduct research analyzing the knowledge, attitudes, and training of community health workers who work to end FGC. In the early stages of my research project, I held interviews with many wonderful leaders of organizations working to end female genital cutting (FGC). I also asked for their assistance in sharing a survey with community health workers within and outside their organization. In one interview, a leader asked me very directly “Why should we do all this work?” It was a valid question; I was requesting their incredibly valuable time and resources. Why should they take time to participate in my research specifically when there is so much important work to be done? Last week, I attended a webinar that answered her question better than I ever could have.

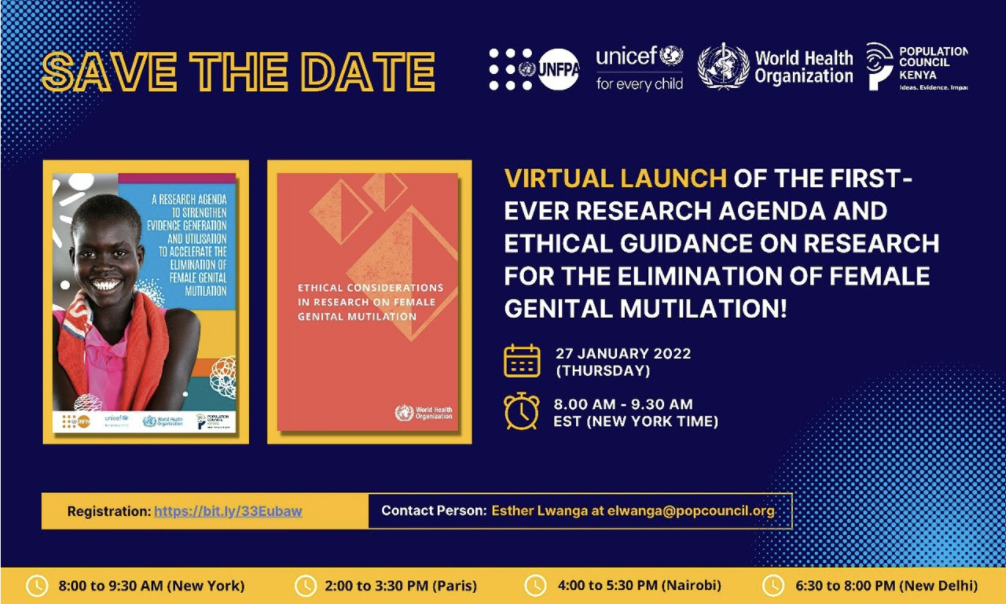

The event was hosted by the UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO, and the Population Council, Kenya. These organizations collaborated to launch two exciting new documents: the first-ever Research Agenda To Accelerate the Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation and Ethical Considersations in Research on Female Genital Mutilation. An opening statement by Nankali Maksud, UNICEF Senior Advisor, described perfectly why these documents are so needed. Every year, at least four million girls are at risk of undergoing FGC. The COVID-19 pandemic has added an additional two million cases to this figure, which otherwise would have been averted. In order to end FGC by 2030, progress needs to be 10 times faster. To achieve this goal, the work to end FGC must be based on high quality evidence, which requires 1) asking the right questions and 2) ethical guidance, both of which are addressed in these documents.

To date, research on FGC prevention and elimination has been limited. The research agenda was created by performing a literature review and developing a list of questions to explore the gaps in our current knowledge. The list is very comprehensive, and the authors even ranked the questions by priority so researchers can clearly see what needs to be addressed most urgently. The document calls on researchers to ask important questions, the top priority being: “How can healthcare providers and the health system be effectively utilised in the prevention of FGM and the provision of services to women and girls affected by FGM?” The complete list of 78 research questions is broken down into thematic areas, including Enabling Legal and Policy Frameworks, FGC in Conflict and Crisis Settings, and more.

The guidelines for ethical considerations when conducting research on FGC includes checklists for each step of the research process to ensure that the rights of participants are prioritized and respected at all times. The document also emphasized the importance of engaging with the community early to ensure that research will make a contribution to the health and well-being of the population. This part is essential. Research is not done simply for the sake of running numbers or getting published—research is only as useful as the extent to which it can guide policies and interventions. We must make sure research is relevant in order to end FGC.

As an FGC researcher myself, I wish these comprehensive guides existed when I began my project, but this will not stop me from using them going forward. I am excited for the future of research under the guidance of these resources. It’s inspiring and hopeful to see multiple organizations come together to support the importance of evidence-based approaches to end FGC.