(Note: The following blog was written by a survivor who attended a meeting, the topic of which was on mental health and FGC. Her story highlights the power of storytelling and how it helps break the isolation that many survivors experience in having undergone FGC and dealing with their trauma afterwards, an isolation that Sahiyo is attempting to break via the storytelling work we engage in with communities.)

By Anonymous

Country: Egypt & United States

Even now, despite my brain trying to convince me it was a good idea to attend a conference on FGM and Mental Health, I cannot emotionally explain what really happened that day. The conference consisted of FGM survivors, human rights advocates, therapists, and policymakers, and almost two weeks after having attended, I started to have stronger flashbacks of the terrible experience I underwent with FGM in my home country, Egypt. I have mixed feelings of love, support, and pain for having attended that conference.

My journey dealing with that horrible experience started in my home country where my rights as a human being were violated without my consent. I was bleeding and almost died having been operated upon twice. Even now, I cannot easily write these words. You may wish to read my full story published here.

The experience of meeting with other survivors from India and other countries was something I strongly needed to help bring me face to face with the many answers to the many questions in my mind regarding why I experienced so much anxiety, sadness, depression, panic, and fear after my cutting. I wanted to know how other survivors had dealt with their FGM especially those who spoke up about it publicly, such as (Mariya Taher, Leyla Hussien, Jaha Dukureh , Naima Abdulhadi, and others) ; I am relatively new to openly talking about it and I still feel as if I am climbing a mountain when trying to share or speak about it. I heard these women saying how it was and is still difficult; and listening to them has helped me to feel that I am not alone in my experience. I saw how powerful the pain of this experience can be, but at the same time was inspired by the courage of what they and I were determined to do. To speak up about FGM openly and to try to prevent it from happening to other girls.

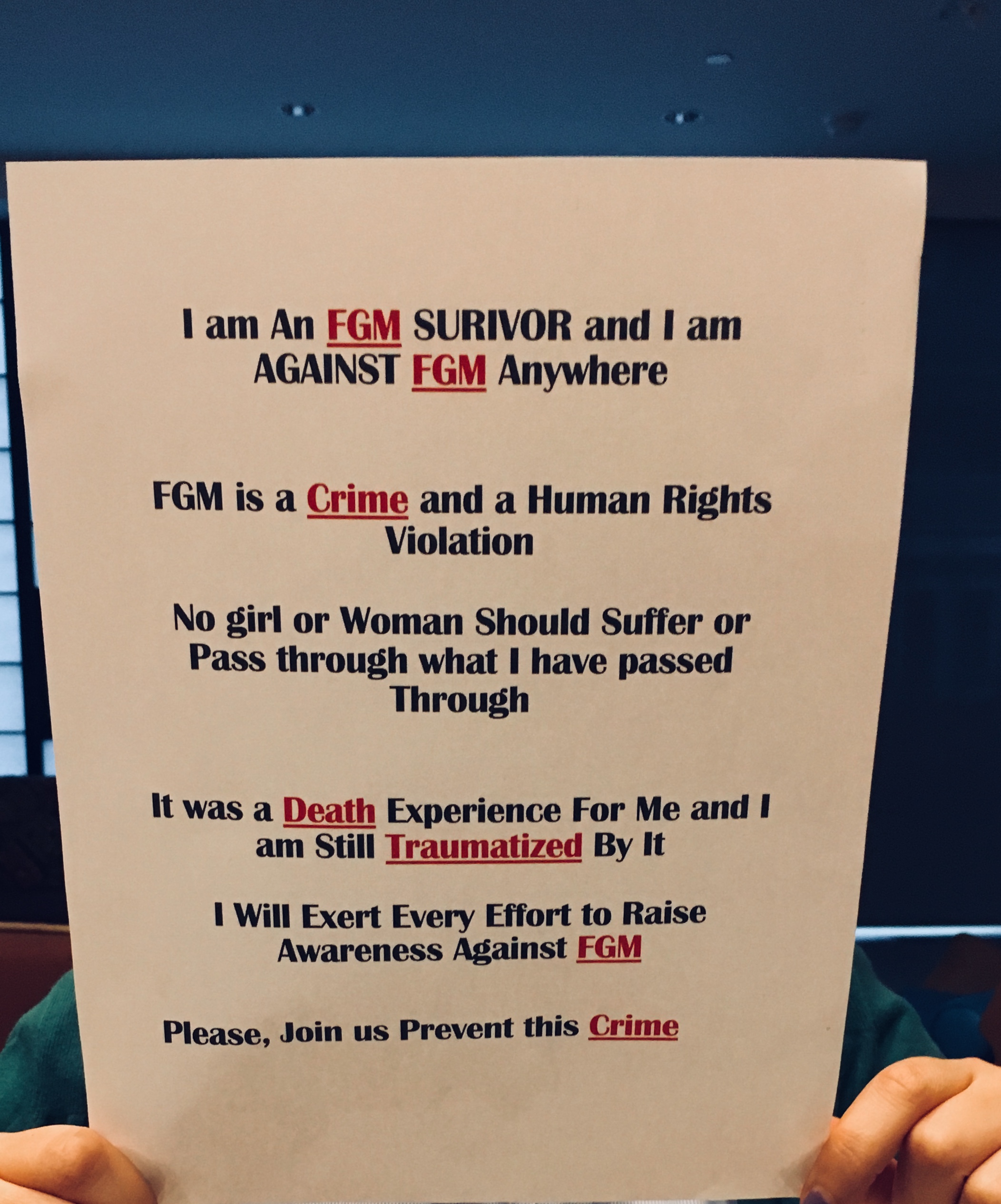

That meeting was the first time I met with and spoke to other survivors from different countries, such as the United Kingdom, Gambia, India, not to mention the United States. At the time, I felt happy that this meeting could serve as a comfort zone for me, knowing others understood what I had gone through. Seeing all those women in that room encouraged me to say amongst the group of almost forty members that I too am a FGM SURVIVOR. I knew these women would not shame me and I did not need to fear being labeled, judged, or threatened for publicly admitting I was a survivor. My heart was beating and my breath was short as if I had climbed a mountain. I thought I was ok during the 8-hour meeting, yet I collapsed and burst into tears at the end; I cannot precisely tell you why, but I thought about how it is unfair that our bodies and souls are violated with this harmful crime. Most of the time I feel sad that I had to go through these painful thoughts, feelings, or flashback of the operation room and after. It feels like I am being retraumatized when something happens to trigger the original trauma of FGM.

I beg every mom and dad to see their daughters as beautiful souls who do not need to be cut to be pure. I am Muslim, and I can say it strongly, clearly, and angrily: Do not make it religious because it is not. My body was not supposed to be violated in this severe way nor was my soul. Yet, both happened. But I am comforted in knowing that there are others who I can talk to who understand my pain. FGM is a crime and more work needs to be done with healthcare professionals, as well as policy makers. Girls must be protected from being cut and survivors should be supported with the needed assistance to help them heal.