By Derrick Simiyu

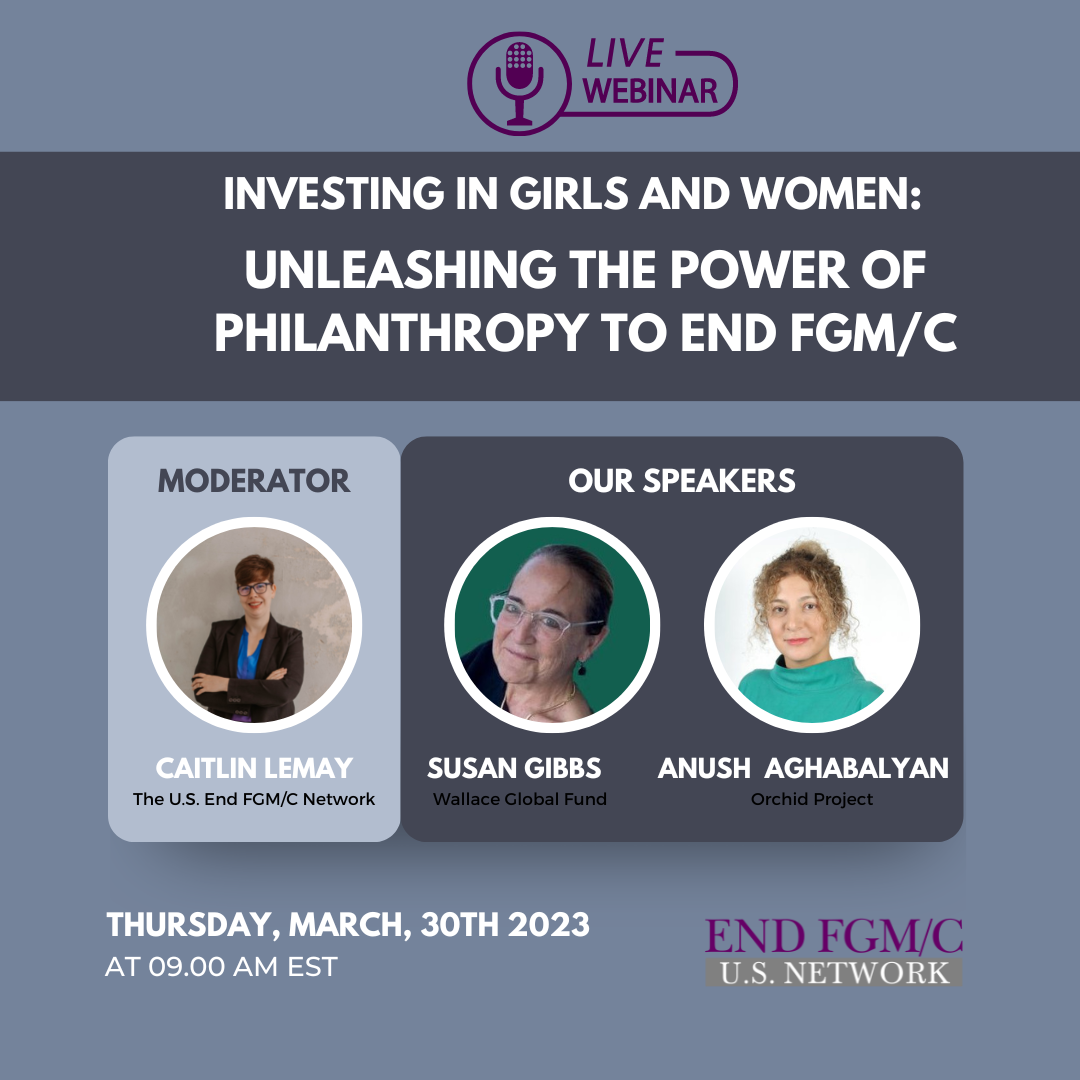

After attending the webinar Investing in Girls and Women: Unleashing the Power of Philanthropy to End FGM/C, I learned about challenges related to funding programs for those affected by FGC; in particular, the fact that little funding is allocated to FGC because it is not prioritized as an urgent problem.

Speakers introduced the ‘funding gap’ of $2.1 billion between what is needed to end the practice globally ($2.4 billion) and what is currently being provided ($275 million). They also highlighted a campaign dedicated to the need for investing in ending FGC.

Asenath Mwithigah, Chief Executive Officer at Orchid Project, elaborated on how to reduce the funding gap, pointing to the need for organizations to be held accountable; she believes accountability would ensure there is no misuse of the funds invested in FGC. Accountability would also help in avoiding the diversion of funds away from their original intention. For example, when the Covid-19 Pandemic arose, funds meant for FGC were diverted into fighting the crisis.

Learning about these funding challenges made me realize that FGC is not addressed with the urgency that it demands. One challenge is that most donors want quick fixes when deciding what programs to invest in, and hence fail to invest in the long-term, multi-year solutions that are really needed to create behavior change to end FGC. Donors may also find it difficult to gauge impact in regard to whether FGC is being prevented for future generations and/or if a community is moving towards abandoning FGC because this harmful social norm is a taboo subject for communities to talk about openly. Most often, programs working on FGC provide evidence of their effectiveness in qualitative terms (e.g. stories) versus quantitative terms (e.g. numerical data), which I was surprised to learn most donors seek. Especially because Sahiyo uses storytelling as such an important tool, I think it doesn’t make sense that most donors would prioritize numbers rather than personal experiences.

I thought anothering intriguing part of the webinar was learning about the challenges in addressing FGC through policy. Every time a new government comes into power in a country, political priorities in terms of governance and policy-making can change. For example, in Tanzania, the government's stance on FGC has shifted over time. Although Julius Nyerere, the nation's first president, spoke out against the practice in the 1960s, succeeding governments were less aggressive in their efforts to curtail it. Once the next government takes office, most of the policies that were in place before become difficult to uphold. Policies and actions designed to prevent FGC may then be ignored and may not be given utmost importance.

What’s next?

I couldn't help but think of this question throughout the webinar as I listened to the speakers. The argument for donor cooperation was made distinctly: if donors pooled their resources to stop FGC, the Sustainable Development Goal #5 of ending FGC by 2030 would quickly be realized. With the pooled funds, community-based organizations like Sahiyo would have increased programming to help end FGC.

My takeaway from the meeting was that in order to close the funding gap, we must channel more resources into ending FGC, but at the same time we must ensure accountability of the funds usage to avoid any wastage. After the meeting, I felt inspired to commit to closing the funding gap by contributing my resources (time, skill-sets, and finances) to ending FGC.