By Madrisha Debnath

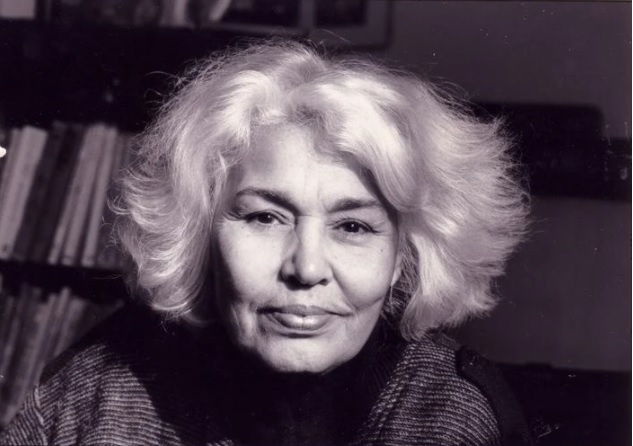

Despite the fact that the mother of Egyptian Feminist Movement Nawal El Saadawi died at age 89 earlier this year, her fight against patriarchy lives on. Born in 1931, she was an Egyptian writer, psychiatrist, physician, and a powerful feminist activist who fought against female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) for many years. In her autobiography, she wrote as a survivor of FGM/C, “Since I was a child that deep wound left in my body has never healed.”

She began her activism in her college days against the cultural institution of the state that promoted FGM/C. In her opinion, when religious institutions gain power, oppression against women of the region increases, and she believed that women are oppressed under all religious institutions. She wrote 47 books on issues that women face in Egypt. Even as she spent three months in prison, she wrote Memoirs from the Women’s Prison with an eyebrow pencil on toilet paper. She is popularly known as the Simone de Beauvoir of the Arab World.

El Saadawi was the founder and president of the Arab Women’s Solidarity Association and co-founder of the Arab Association for Human Rights. She has been awarded an honorary doctorate from Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium; Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium; and the National Autonomous University of Mexico. She won the North-South Prize from the Council of Europe in 2004, Stig Dagerman Prize in 2011, and has been featured in BBC’s 100 women of 2015 to name a few.

In 1972 she wrote the book Women and Sex in which she criticized FGM/C. Her book became a foundational text of second-wave feminism. The book was banned in Egypt and consequently, she lost her job as the director general of public health for the Egyptian Ministry of Health. In 1980 she yet again wrote about her experience of undergoing a cliterodectomy in her book The Hidden Face of Eve: Women in the Arab World. She was the founder of the Health Education Association and the Egyptian Women Writers’ Association and was the Chief Editor of Health Magazine in Cairo, and Editor of Medical Association Magazine.

As she graduated as a medical doctor from Cairo University in 1955 she observed that women’s physical and psychological problems are actually deeply rooted in the religious and cultural institutions they belong to. She connected oppressive cultural practices and norms of the society to the systemic oppression under the structures of class, patriarchy, and imperialism. While working as a doctor in Egypt she became aware of the issue of domestic violence and inequalities that women face in their day to day life. After trying to protect one of her patients from domestic violence, she went back to Cairo and eventually became the director of the Ministry of Public Health. As a feminist and a doctor, she was against male circumcision. In her view, she did not separate cutting children from a physical or social point of view. In an interview with The Independent she said, “I am going to carry on this forever.” Her legacy will live on for future generations to consider.