(This article is Part 3 of a seven-part series on trauma related to Female Genital Cutting. To read the complete series, click here. These articles should NOT be used in lieu of seeking professional mental health and counseling services when needed.)

By Joanna Vergoth, LCSW, NCPsyA

Trauma overwhelms us and disrupts our normal functioning, impacting both the brain and body, both of which interact with one another to regulate our biological states of arousal. When traumatized, we lose access to our social communication skills and displace our ability to relate/connect/interact with three basic defensive reactions: namely, we react by fighting, fleeing, or freezing (this numbing response happens when death feels imminent or escape seems impossible).

In order to understand and appreciate our survival responses, it’s important to have a basic understanding of how our brain functions during a traumatic experience, such as undergoing Female Genital Cutting or FGC.

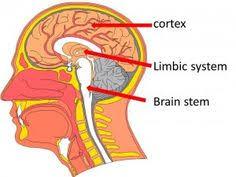

Our brains are structured into three main parts:

The human brain, which focused on survival in its primitive stages, has evolved over the millennia to develop three main parts, which all continue to function today. The earliest brain to develop was the reptilian brain, responsible for survival instincts. This was followed by the mammalian brain (Limbic system), with instincts for feelings and memory. The Cortex, the thinking part of our brain, was the final addition.

The Reptilian brain:

The reptilian brain, which includes the brain stem, is concerned with physical survival and maintenance of the body. It controls our movement and automatic functions, breathing, heart rate, circulation, hunger, reproduction and social dominance— “Will it eat me or can I eat it?” In addition to real threats, stress can also result from the fact that this ancient brain cannot differentiate between reality and imagination. Reactions of the reptilian brain are largely unconscious, automatic, and highly resistant to change. Can you remember waking up from a nightmare, sweating and fearful—this is an example of the body reacting to an imagined threat as if it were a real one.

The Limbic System:

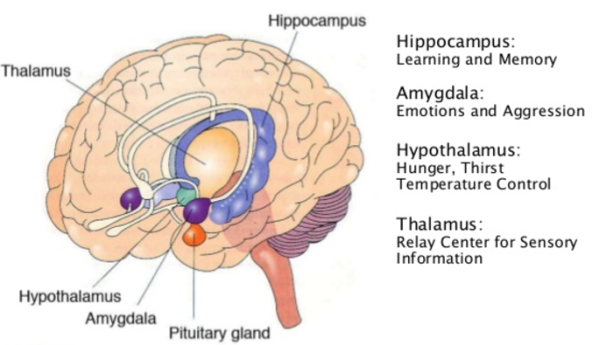

Also referred to as the mammalian brain, this is the second brain that evolved and is the center for emotional responsiveness, memory formation and integration, and the mechanisms to keep ourselves safe (flight, fight or freeze). It is also involved with controlling hormones and temperature. Like the reptilian brain, it operates primarily on a subconscious level and without a sense of time.

The basic structures of Limbic system include: thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus and hypothalamus

The Neocortex:

The neocortex is that part of the cerebral cortex that is the modern, most newly (“neo”) evolved part. It enables executive decision-making, thinking, planning, speech and writing and is responsible for voluntary movement.

But…

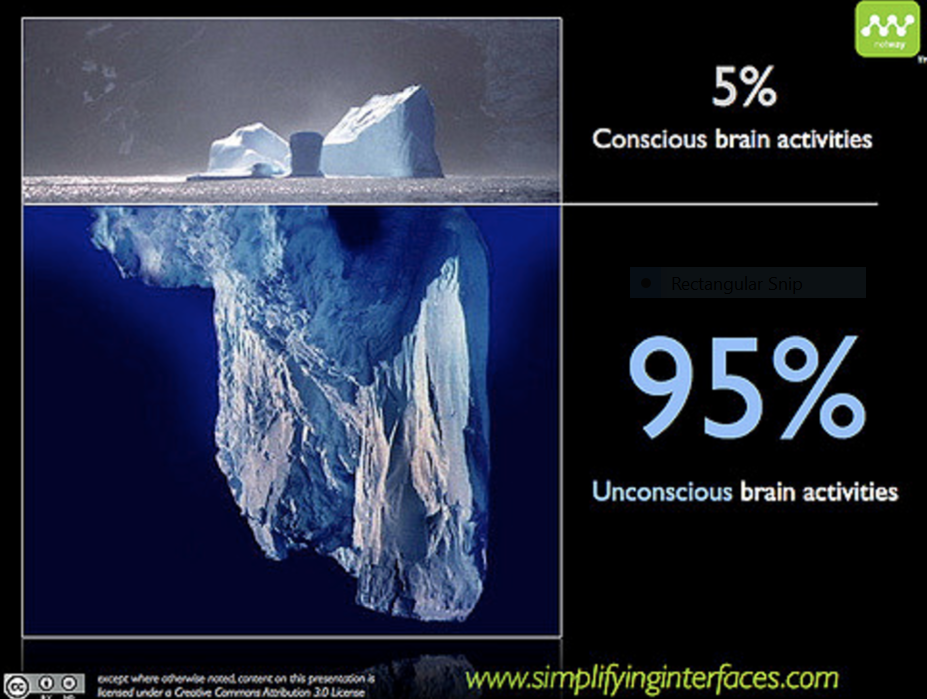

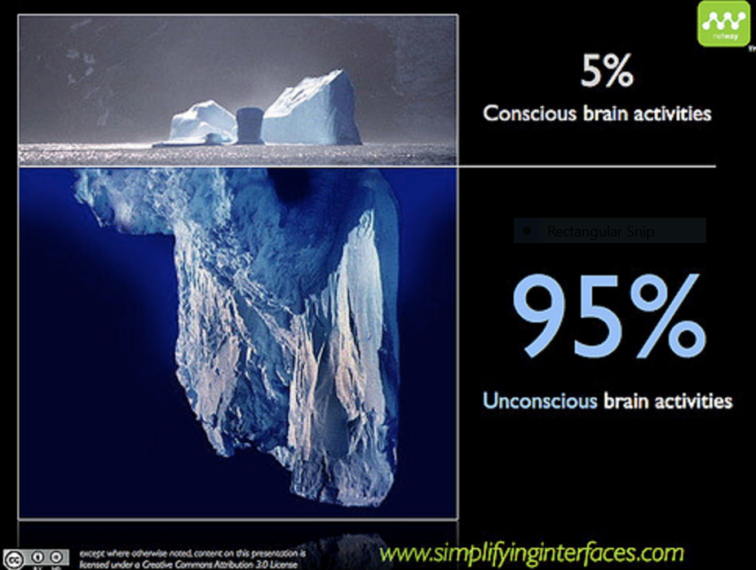

Almost all of the brain’s work activity is conducted at the unconscious level, completely without our knowledge. While we like to think that we are thinking, functioning people, making logical choices, in fact our neocortex is only responsible for 5-15 % of our choices. When the processing is done and there is a decision to make or a physical act to perform, that very small job is executed by the conscious mind.

How the brain responds to Trauma

The fight or flight response system — also known as the acute stress response — is an automatic reaction to something frightening, either physically or mentally.

This response is facilitated by the two branches of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) called the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) which work in harmony with each other, connecting the brain with various organs and muscle groups, in order to coordinate the response.

Following the perception of threat, received from the thalamus, the amygdala immediately responds to the signal of danger and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is activated by the release of stress hormones that prepare the body to fight or escape.

It is the SNS which tells the heart to beat faster, the muscles to tense, the eyes to dilate and the mucous membranes to dry up—all so you can fight harder, run faster, see better and breathe easier under stressful circumstances. As we prepare to fight for our lives, depending on our nature and the situation we are in, we may have an overwhelming need to “get out of here” or become very angry and aggressive (See ‘I underwent female genital cutting in a hospital in Rajasthan’ on Sahiyo’s blog). Usually, the effects of these hormones wear off only minutes after the threat is withdrawn or successfully dealt with.

However, when we’re terrified and feel like there is no chance for our survival or escape, the “freeze” response, activated via the parasympathetic nervous system, can occur. The same hormones or naturally occurring pain killers that the body produces to help it relax (endorphins are the ‘feel good’ hormones) are also released into the bloodstream, in enormous amounts, when the freeze response is triggered. This can happen to people in car accidents, to sexual assault survivors and to people who are robbed at gunpoint. Sometimes these individuals pass out, or mentally remove themselves from their bodies and don’t feel the pain of the attack, and sometimes have no conscious or explicit memory of the incident afterwards. Many survivors of female genital cutting have reported fainting after being cut. Other survivors have reported blocking out their experiences of being cut (See ‘I don’t remember my khatna. But it feels like a violation’). Our bodies can also hold on to these past traumas which may be reflected not only in our body language and posture but can be the source of vague somatic complaints (headaches, back pain, abdominal discomfort, etc.) that have no organic source. FGC survivors who were cut at very young ages can be plagued with ambiguous symptoms such as these.

Neuroscientists have identified two different types of memory: explicit and implicit. The hippocampus, the seat of explicit memory, is not developed until 18 months. However, the implicit memory system, involving limbic processes, is available from birth. Many of our emotional memories are laid down before we have words or explicit recall, yet they influence our lives without our awareness. Although a traumatized person may not explicitly remember the traumatic event(s), the memory is held in the body: ‘‘What the mind forgets, the body remembers in the form of fear, pain, or physical illness’’ (Cozolino, 2006, p. 131; Van der Kolk, 1994).

The brain and PTSD

For those affected by Post Traumatic Stress Disorder — especially those who had no chance to fight back successfully or escape — the body and the brain have been blocked from responding normally and the trauma does not end.

Dr. Bessel van der Kolk (2001), a major clinician and researcher in the field of trauma notes that individuals with PTSD ‘‘are very sensitively tuned to pick up threat and respond to minor stimuli as if their life were in danger”.

What Dr Bessel is referring to is the fact that for those with PTSD, the trauma has not been able to come to a conclusion and remains unfinished. When stressors are present or familiar triggers (such as a person, place, or scent) are activated, the person can feel threatened and those fight-or-flight reactions stay turned-on, prompting the amygdala to be in a state of perpetual overactivation — in effect, hijacking the thinking process. Some FGC survivors in the Bohra community have experienced versions of such responses. For example, one young woman interviewed in the documentary A Pinch of Skin mentioned that her traumatic memories of being cut are triggered when she sees her cutter in the neighbourhood, and she ‘never wants to see that lady again’.

When the amygdala is overactive and in control it registers only emotional and sensory information so that when the hippocampus tries to record the event sequentially it is compromised by these hormonal releases and only fragmented flashes of memory and emotional distress are remembered. This, too, is common in the way many FGC survivors remember their experience of being cut.

Why this happens

Trauma impairs the integrative functioning in the brain and neural networks get stuck in paths related to processing and encoding fear. The limbic system stores our emotional memories and replicates the response we had to the earliest time we experienced a similar situation: if we are in a state of distress we will revisit a memory of distress and that will cause more somatic sensations of distress.

PTSD reflects a condition in which the body’s natural mechanisms for recovery have failed, resulting in a prolonged state of negative stress arousal—causing increased heart rate and blood pressure, restricted flow of blood to the genitals and digestive systems—in effect making it hard to process information, eat, sleep, salivate or be sexually aroused.

For more information about the Psychosexual Consequences of trauma, see Trauma and Female Genital Cutting, Part 4: Psychosexual Consequences.

About Joanna Vergoth:

Joanna is a psychotherapist in private practice specializing in trauma. Throughout the past 15 years she has become a committed activist in the cause of FGC, first as Coordinator of the Midwest Network on Female Genital Cutting, and most recently with the creation of forma, a charity organization dedicated to providing comprehensive, culturally-sensitive clinical services to women affected by FGC, and also offering psychoeducational outreach, advocacy and awareness training to hospitals, social service agencies, universities and the community at large.