by Aarefa Johari

This August, the Population Council and UK Aid published a unique, comprehensive report on Female Genital Cutting around the world, to serve as a valuable resource for anyone working to bring the practice to an end. Titled ‘A State-of-the-Art Synthesis on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting – What do we know now’, the report provides a zoomed-out analysis of all the recent available data on FGC from the 29 countries that have done national surveys on the subject. Although India does not feature in this list, the report offers plenty of food for thought for those of us in South Asia in general and the Dawoodi Bohra community in particular.

In hospitals or in homes?

The 29 countries studied in the Population Council report are all from Africa, except for Yemen and Iraq. But the report also acknowledges the prevalence of the practice in other countries like India, Pakistan, Oman, Malaysia, Iran and Colombia, where no national surveys have been done yet. Indonesia, where the widespread prevalence of FGC has only recently been given official recognition, has been featured prominently in the report.

Types I and II are the most common forms of FGC around the world, and in the 29 countries studied in the report, it was found that the cutting is still overwhelmingly performed by traditional cutters. In the Bohra context, we do not know if that still holds true.

We know for sure that in India, in big cities like Mumbai, nearly all Bohras who still choose to get their daughters cut end up going to Bohra-run hospitals or clinics. Based on anecdotal information, we also know that Bohras in smaller towns are increasingly choosing to have it done by a local doctor. For instance, one woman from a Bohra housing colony in Jamnagar told a Sahiyo founder that khatna for girls is now performed in clinics because with the traditional untrained cutters, there had been many instances of “cases going wrong”.

This is disturbing for two reasons: One, khatna is now increasingly getting medicalised among Bohras, creating the entirely false impression that it is a medically sanctioned and beneficial practice. In truth, khatna has no proven health benefits at all. And two, we cannot help but think of the girls behind the many “cases that went wrong”. The word “case” is a medicalised euphemism for an actual girl, now probably a grown woman, who must have been cut more than intended, who might still be experiencing physical, psychological and/or sexual trauma that has probably never been addressed, because we are taught to be silent about these matters and because our country does not have adequate mental health resources to help those in need.

How many such “cases gone wrong” have we had in the Bohra community? No one knows, because for centuries, the voices of those girls and women have been silenced. Supporters of khatna often claim that only a “small number” of Bohra women have suffered negative consequences. But if just one town in Gujarat has seen “many” cases that went wrong, perhaps it is time to drop our defenses, create a positive space for all women to share their stories, and truly listen to their voices.

Why is khatna practiced anyway?

The Population Council report also makes an interesting point about the reasons different communities give for practicing FGC. Across cultures, there are a variety of reasons given, which can be broadly classified into certain basic themes: marriageability, chastity, social status, religious identity, transitioning into womanhood, maintenance of family honour, beauty and hygiene. But unlike popular belief, the reasons given by a particular culture or community do not remain static – “as with other social norms or practices, they are dynamic and subject to change and influence over time”.

This rings true for Dawoodi Bohras around the world, where the reasons given for practicing khatna can change from one family to another. Two of the most commonly cited reasons are “it is in the religion” and “it moderates sexual urges and prevents promiscuity”. “Cleanliness and hygiene” is cited far less frequently, even though it is the “official” reason as per the Bohra religious text Daim al-Islam. This is most likely because khatna is carried out secretly, Bohra religious leaders have never publicly discussed or advocated for the practice and women have typically passed down the reasons for it as an oral tradition within their families.

And some Bohras are now rationalising khatna in ways that their grandmothers probably did not – some compare it to male circumcision and claim that it prevents urinary infections and/or sexually transmitted diseases; others have started equating it with the medical procedure of clitoral unhooding and claim that the removal of the hood enhances sexual pleasure.

This just goes to show that it really doesn’t matter what religious texts like Daim al-Islam or the Sahifo may say about khatna for girls. Most community members don’t seem to even be aware of what these texts say, and they have been cutting their girls for entirely different reasons. One of my own aunts once told me that girls who are not cut will turn into prostitutes – a preposterous idea that she not only believes in, but also attributes to the Prophet! The sad truth is, her daughter was cut for this reason – to prevent her from becoming a prostitute – and not for any “official” reason. Similarly, other girls are being cut to keep them chaste, and I was cut for no reason at all, because my mother just didn’t think of questioning the practice.

Hope for the future

The Population Council report also points out that FGC often continues within a community because the individual preferences of girls or even their mothers are “often superseded by those of elder women in the family”. Among Bohras, we keep hearing from scores of women who have experienced the same dilemma: they didn’t want to have their seven-year-old daughters cut, but eventually had to cave in to pressure from their own mothers or mothers-in-law. Many Bohra women are currently facing the same problem and are unsure of what to do.

The most promising fact emerging from the report, however, is that in several FGC-practicing countries, the majority of already-circumcised women are now opposed to the practice or are unsure of whether to continue it. The graphs are similar for men in many FGC-practicing countries – the majority of these men do not support the continuation of the practice.

And we know for sure that this is very true for the Bohras all over the world. In the past year itself, the number of Bohra women and men speaking out about khatna, and asserting that they will not cut their children, has exploded. Some have spoken out openly, but many more are reaching out to us privately, on a regular basis, to offer their support to this unprecedented movement.

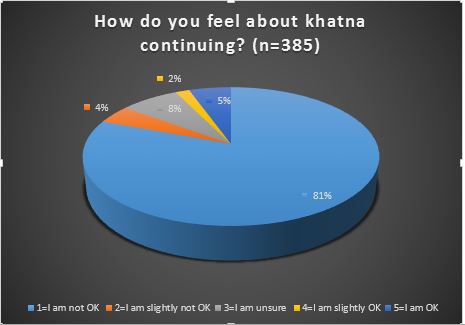

Sahiyo’s online survey of Dawoodi Bohra women – which you will be hearing more about in the coming months – also revealed a positive trend in women wanting khatna to stop

So we can be sure that a generation from now, we will be a lot closer to building an FGC-free world than we were ever before!