By Aarefa Johari

(A shorter version of this piece was published on the British Medical Journal’s blogs site on January 20, 2017. Read it here.)

Two years ago I met Sara (name changed), a bright mother of two and a member of the Dawoodi Bohra community in Mumbai. From the time her daughter was a baby, Sara was determined she would not put her child through the ritual of khatna – female circumcision – that is considered mandatory for all Bohra girls. She had heard too many times that khatna is done to curb a girl’s sexual urges, and she was completely against the practice.

But when her daughter turned six, family pressure began to mount. Her mother-in-law was adamant that the child had to be cut at the age of seven, and after months of trying to resist, Sara finally caved in. She saw no choice but to have her daughter circumcised, so she decided to do everything in her power to ensure that khatna didn’t leave her little girl traumatised. No traditional, untrained “cutters” who use razor blades or knives to slice the clitoris; she wouldn’t even take her daughter to just any Bohra doctor authorised to perform khatna. Instead, Sara sought out a gynaecologist who agreed to completely sedate the child during the procedure.

Female circumcision, known around the world as Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM or FGC), is recognised as a human rights violation by the World Health Organisation. It involves cutting or altering parts of the female genitalia for non-medical reasons. There are various types of FGC practiced around the world, with varying degrees of severity. The kind that Bohras practice – cutting all or part of the clitoral hood – falls within WHO’s definition of Type 1 FGC. The practice is illegal in at least 40 countries, because there are no medical benefits to cutting any part of the female genitalia. In fact, even the mildest form of FGC can have harmful health consequences, including bleeding, swelling, painful urination, infection and reduced sexual sensitivity.

And yet, just two years ago, Sara’s seven-year-old daughter was cut in an operation theatre in a Mumbai hospital, by a licensed gynaecologist who administered general anaesthesia on the child so that she would have no memory of her clitoral hood being removed without consent.

If most doctors and medical associations in India are unaware of such incidents, I wouldn’t be surprised. Until a few years ago, almost no one had heard of Female Genital Cutting being practiced in India. Even international campaigns against FGM/C focused mainly on Africa, and only in the last few years has it been acknowledged that FGC is globally prevalent. But in India, Bohras have been secretly circumcising their daughters for centuries. Like so many seven-year-old Bohra girls, I was cut as a child too.

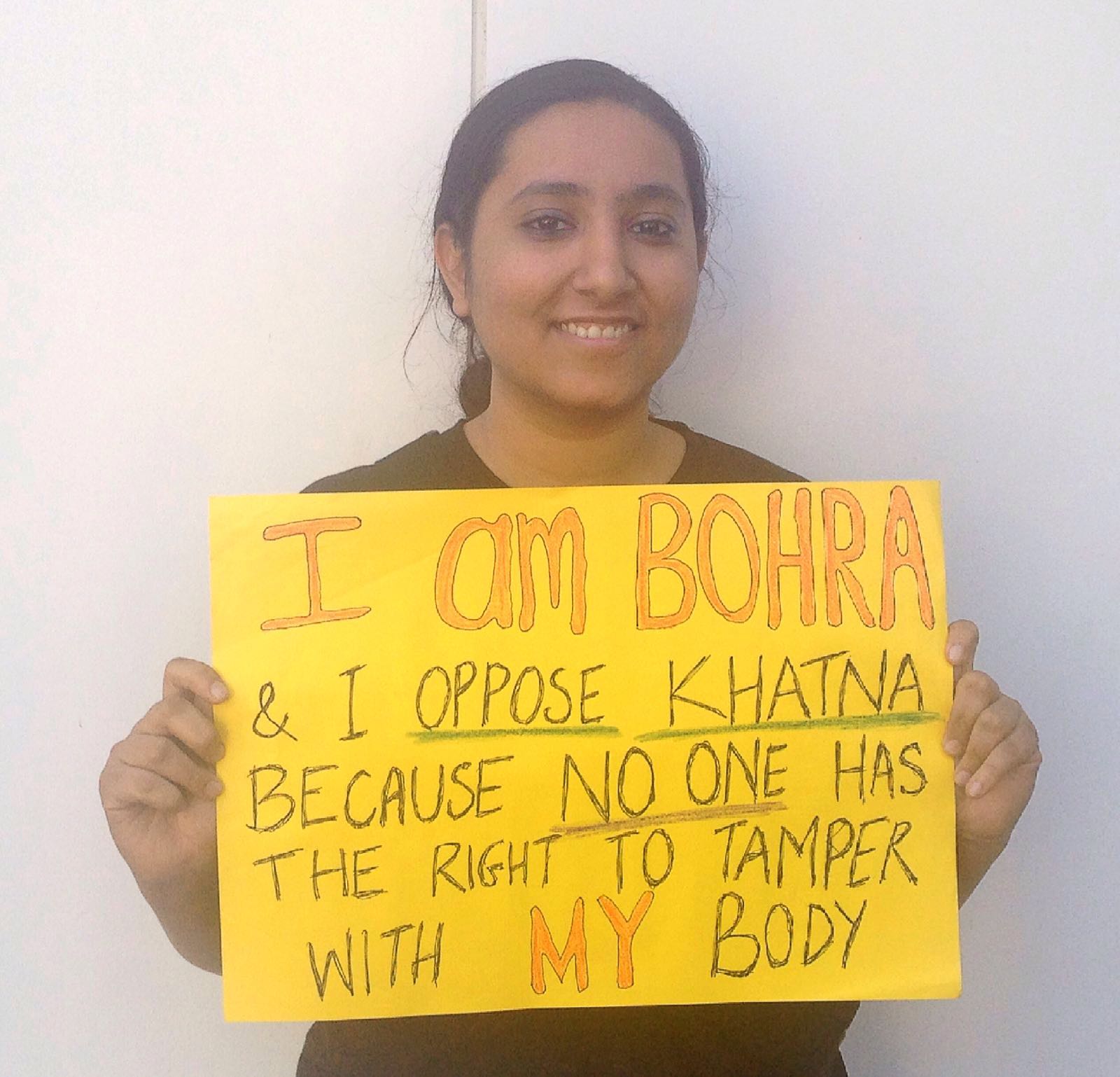

We are not a large community – barely two million in number – but those familiar with Dawoodi Bohras know us as a close-knit, well-educated, wealthy business community with a reputation for being progressive towards women. But the Bohras are the only group known to practice FGC in India so far. Other Indian Muslim sects don’t even consider the ritual Islamic, because there is no mention of it in the Quran.

Bohra families, depending on who you speak to, give a variety of different reasons for practicing female khatna. “It is in the religion”, “it curbs sexual desire” and “it prevents pre-marital and extra-marital affairs” are the most common justifications; other reasons include hygiene and health, specifically the prevention of urinary tract infections and other diseases. Medically, of course, there is no proof of such claims.

More recently, some Bohras have begun rationalising khatna with the strangest argument: they claim it is the same as “clitoral unhooding”, a surgical procedure that a number of doctors in Western countries perform on adult women to enhance sexual pleasure. I first heard this argument from Sara, a few months after her daughter was cut. The child may have been sedated in the OT, but the mother was still deeply uncomfortable with her khatna. After the “surgery”, Sara spent hours online trying to understand what exactly had been cut and why. She then came across a website on clitoral unhooding. It claimed that by removing the hood covering the clitoral glans, the clitoris is more exposed and thus experiences more stimulation and pleasure. Sara shared the website with another Bohra doctor who performs khatna. “Yes, this is exactly what our khatna is. It is done to enhance sexual pleasure,” the doctor claimed.

This affirmation came as solace for Sara – her daughter was not harmed after all, and khatna turned out to have a “positive” intention. Her maternal relief was blind to the gaping holes in this “clitoral unhooding” theory, which were obvious on the website itself. As a surgical procedure, unhooding is recommended only for some sexually active women, if they have excess prepuce tissue that hinders orgasms by preventing the clitoral glans from protruding during arousal. Otherwise, the hood serves important function of protecting the clitoris from over-stimulation or abrasions.

Unfortunately, now that there is a growing movement against FGC within the community, many khatna supporters are trying to promote clitoral unhooding as a “scientific” justification for cutting all seven-year-old girls without consent. If this isn’t enough to mislead parents, we are also witnessing another disturbing trend: the medicalisation of khatna.

Medicalisation refers to the trend in which the cultural, non-medical practice of FGC is increasingly performed by a trained medical practitioner instead of an untrained traditional cutter. For several years now, Bohras in bigger cities like Mumbai have been getting their daughters cut by doctors (though not necessarily gynaecologists) in Bohra hospitals or clinics. They have come to realise that untrained cutters are not only unhygienic, but are also more likely to cut more than intended – particularly if the child is kicking or resisting the cut. The trend is now also spreading to smaller cities and towns. A few months ago, I met a Bohra woman in Jamnagar, Gujarat, who told me, “We’ve stopped going to cutters now because there were too many cases going wrong at their hands.”

Undoubtedly, a doctor will perform khatna in a safer manner than a neighbourhood aunty with a blade. But medicalisation also promotes the entirely false idea that FGC, even in its mildest form, is medically beneficial and acceptable. Not all Bohras are affected by khatna in a uniform manner, and many say they have faced no negative consequences. But in the past five years, with the silence around this tradition gradually breaking, we have heard innumerable stories of women who have been physically, psychologically and sexually scarred by their circumcisions in a variety of ways. Some women bled for days after their khatna and endured lasting pain; many have been unable to forget the mental trauma of being betrayed by their mothers, held down and abused; some have had to seek therapy to be able to get intimate with their partners and many claim they don’t feel easily aroused by clitoral stimulation.

What is a doctor’s responsibility, then, in the face of such a ritual? Two of the most basic pillars of medical ethics are to do no harm and to act in the best interests of a patient. Female circumcision has no health benefits and can potentially harm girls and women. For a patient, it serves no scientific or medical interest to have any part of the clitoris removed. In fact, since khatna is not a medical procedure at all, girls being brought to get cut can hardly be called patients. Besides, a seven-year-old is not capable of giving informed consent to a procedure that permanently alters one of her most vital sexual organs.

Some doctors I know are already discouraging parents from getting their daughters circumcised. But others carry out khatna on little girls even if they are aware that it has no medical standing. “There is no point asking whether it [khatna] is right or wrong – we have to do it anyway,” said one Bohra gynaecologist I spoke to a few years ago. If a doctor herself adopts this perspective, what happens to medical ethics and scientific temper?

Now that the practice of FGC among Bohras is no longer a secret, perhaps it is time for medical bodies and doctors’ associations to take an official stand on the subject. There are already scores of activists working to end khatna by spreading awareness within the community. In a few years, India might even have a law against the practice. But strong medical opinion is just as important. Because in a few years, Sara’s second daughter will turn seven. And in the name of “scientific” clitoral unhooding, she intends to get this child circumcised too.

If the medical fraternity publicly and vocally condemns this practice, this girl – and many more – could be saved from the blade.