By Umme Kulsoom Arif

In response to your letter published in The Detroit News, “Dawoodi Bohra Women of Detroit speak up,” I write to you as a woman who grew up in a part of the Dawoodi Bohra community, just like you. I am also a woman of faith and education, a woman who loves her country as well as her Dawoodi Bohra community, who balances religion and patriotism in a trying, divisive time. And just like you, I am frustrated and saddened by the propaganda and misinformation that has spread surrounding the case of Dr. Jumana Nagarwala because I too am a survivor. A survivor of a harmful practice that violated my human rights, robbed me of my personal integrity, and — in punishing me for my own femininity — left me permanently scarred, both mentally and physically: khaftz.

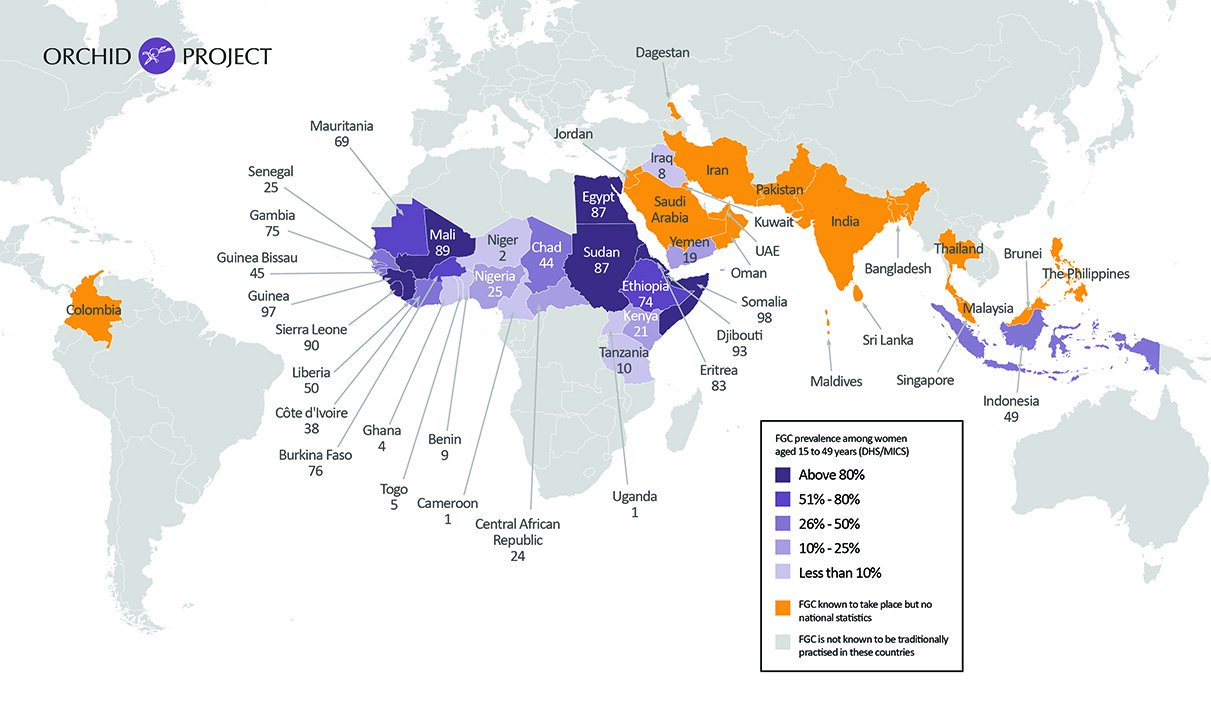

You claim that khaftz “in no way can be defined as female genital mutilation,” but do you know what FGM even is? The World Health Organization defines FGM/C as “all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.” So educate me, then — what is the medical reason for khaftz? Why must it be done? Why must a girl be lied to, held down, or drugged so that a blade can be taken to her genitals and a part of her clitoris sliced away?

You call the procedure “harmless,” so I ask you — where does the harm begin in your minds? Where do you draw the line between the “ritual” you defend and the “more barbaric practices from around the world” you claim to condemn? Is it not harmful to deny your daughter the right to her own bodily autonomy? Is it not harmful to violate her right to be free of torture and degrading treatment and to teach her that her body is “wrong” and must be surgically altered based on the words of religious men?

The Quran does not ask this of us, so I ask you — who does? When countries around the world — including the United States — have signed human rights treaties both condemning and outlawing all forms of FGM, who demands that our daughters be subjected to a cutting or scraping without their consent and with no medical reasoning behind it?

Though you claim to be patriotic Americans who follow all the laws of the land, you challenge a law meant to protect the most vulnerable members of the country’s population — its children. How can you in good conscience, claim that khaftz is “much more akin to a body piercing” when a child would never consider getting a piercing in such a sensitive area?

Many of you are lucky to have suffered no consequences — physically or mentally — from khaftz, but your experiences are far from universal. You lie to yourselves when you purport to be representative of all the survivors of the khaftz. You lie to your daughters when you claim that there are no negative effects to the practice. You do a disservice to your community when you hide the truth of this harmful form of gender-based violence behind pleas for tolerance and claims of political persecution. By claiming that your experiences are universal and by defending this harmful practice, you have a direct hand in perpetuating violence against women.

Is that the future of the Dawoodi Bohra community? A future where we must look our children in the eyes and tell them that they have no ownership of their bodies? A future where our daughters must be subjected to sexual trauma and placed at risk for future infection, for future complications in childbirth, or for chronic pain in a most sensitive area? The Dawoodi Bohra community cannot adhere to archaic violence in the name of tradition. The world around us has changed, and today we know more about our bodies and the consequences of our actions than we ever did. We must grow as people, as a community. We must come together to help, not harm.

You may be educated women, but you blind yourself to the true nature of khaftz and its harm. You beg for tolerance and understanding but you do not try to understand the pain you inflict on your daughters when you have them cut. I beg you to take the time to listen to women the world over who have been harmed by khaftz.

Read also “Other Views on FGM.”

Maryah Haidery talking at the Washington DC screening.

Maryah Haidery talking at the Washington DC screening.

![DOgkHoYWsAAwp8a[1]](/images/description/dogkhoywsaawp8a11.jpg)