Syedna Mufaddal Saifuddin’s recent wa’az (sermon) in Mumbai has come as a disappointment. For almost three months now, Dawoodi Bohras who wish to see an end to female circumcision (khatna) had been hopeful. Starting with Sydney in February, many Bohra jamaats in different cities around the world have issued letters to their members, asking them to stop practicing khatna because it is against the law in those countries. (Read more about the jamaat letters here.)

The jamaats issuing these letters – be it in Australia, USA, UK or Sweden – are all trusts that function with the sanction of the central Bohra leadership, whose headquarters are at Badri Mahal in Mumbai. The jamaat letters gave hope to Bohras across the world, even in countries like India and Pakistan where there are no laws against female genital cutting, that the Bohra leadership would eventually ask the whole community to stop practicing khatna.

After all, in a community that is so close-knit and centralised, why should girls in some parts of the world be spared from circumcision, while girls in other countries continue to be cut? If Dawoodi Bohras are one community, how can there be different rules based on geography?

In this light, the Syedna’s recent public sermon on April 25 has left large sections of Bohras surprised and disheartened. His speech, given at Mumbai’s Saifee Masjid on the occasion of the death anniversary of 51st Syedna Taher Saifuddin, made an indirect but fairly clear reference to khatna.

A four-minute audio clip of that section of the sermon has been circulating among Bohra social media groups all week, and several concerned community members wrote to Sahiyo to tell us that they had attended the wa’az and were shocked by the Syedna’s statements. On April 29, The Times of India wrote a report about these statements, which can be read here.

In the sermon, delivered in the Lisan-ul-Dawat language, Syedna Mufaddal Saifuddin can be heard saying the following:

“Whatever the world says, we should be strong and firm…whatever they say, it does not make a difference to us, we are not willing to accept [what they say]…we are not willing to talk to them. What are they telling us? That what we are doing is wrong?…who are they to teach us?”

The Syedna then makes a reference to other vices that people have, such as drugs or cigarettes, asking, “Why don’t they tell those people [that they are wrong]?”

A clearer reference to khatna comes with the following words in the speech:

“It must be done. If it is a man, it can be done openly and if it is a woman it must be discreet. But the act must be done. Do you understand what I am saying? Let people say what they want…but Rasoolullah [Prophet Mohammed] has said it…Rasoolullah will never say anything against humanity. He has only spoken [of] what is beneficial…from the perspective [“haisiyat”] of the body and the soul. What do they say?…that this is harmful? Let them say it, we are not scared of anyone.”

The Syedna’s sermon is significant for many reasons. This is the first time that he has made such a clear reference to khatna in public without explicitly spelling it out. All through the recent Australia case hearings as well as the anti-khatna campaigns by Sahiyo, Speak Out on FGM and other Bohras, the community was eagerly awaiting a word on the subject directly from the Syedna.

But his declaration that Bohras must continue the act, irrespective of opposition from various quarters, indicates that Bohra authorities were not being sincere when they issued various jamaat letters around the world. The implication of his speech is that the jamaat letters asking people to stop khatna are insignificant – a mere formality to save Bohras from facing criminal consequences in countries where female genital cutting is illegal.

Were the jamaat letters a mere pretence to hoodwink international governments? His speech says “the act” must be done openly for men and discretely for women. Why?

The Syedna says that the “the act” must be practiced because the Prophet recommended as something beneficial. But according to the jamaat letters issued with the sanction of the Syedna, the Prophet also preached the value of “hibbul watan minal imam” – love and loyalty for the laws of one’s country. So which teachings of the Prophet must Bohras in those countries follow?

Most significantly, we would like to point out one thing: the Syedna’s speech dismisses and rejects all opposition from “them”, from all those saying that khatna is harmful and must not be practiced. The “they” he is referring to, however, are not just governments of countries like Australia or the USA.

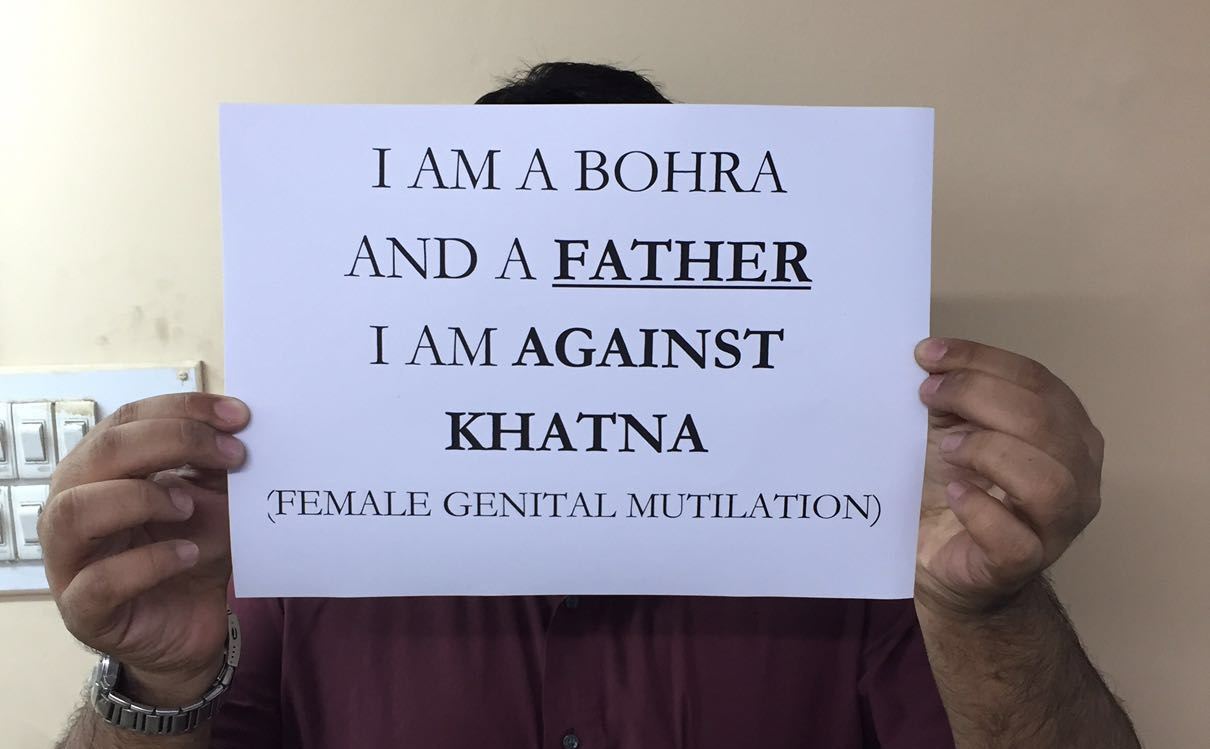

The strongest form of opposition to khatna is now coming from within the community – from Bohra women who have either undergone khatna or have seen their loved ones go through it, and from Bohra men who are horrified that their daughters, sisters, mothers and friends have to go through the cut. These are Bohras of all hues – staunch believers, regular masjid attendees, occasional attendees, sceptics, liberals, traditionalists, reformists – but they are Bohras, and they no longer want the practice of khatna to continue. By alienating these women and men as “they”, as outsiders, the opposition cannot be wished away.Those opposed to the practice have strong reasons for their views, and we urge the Syedna and all Bohras to engage in meaningful debates and discussions on the issue, rather than trying to shut out opposition.

Lastly, the Times of India report quotes a source close to the Bohra authorities, claiming that this speech was not about khatna and has been misinterpreted. However, hundreds of Bohras have interpreted his speech as a reference to khatna and circulated the audio clip widely. If the leadership believes that all of these people misinterpreted the speech, we urge the Syedna to publicly clarify this, and make his stance on khatna clear.