By Megan Seaver

An essential part of the work to end female genital cutting (FGC) is to engage in community-based activism, which means to serve a specific group of people with a specific set of needs and values. Sahiyo’s Editorial Assistant Urvashi Sharma interviewed Saza Faradilla, a community-based activist in Singapore, to discuss how she engages in community-based activism when it comes to the campaign to end FGC.

Saza began the conversation with an explanation for her centralized, community-based approach to ending FGC in Singapore:

“We started End FGC Singapore in November 2020, primarily because we believed that a cohesive, more ordered force needed to be established to bring an end to this practice.” From there, the first step was to “raise awareness among the Muslim community,” then “to lobby officials who occupy high positions of power,” and finally “to facilitate solidarity among Singaporeans in order to create an understanding that this…is a Singapore health problem.”

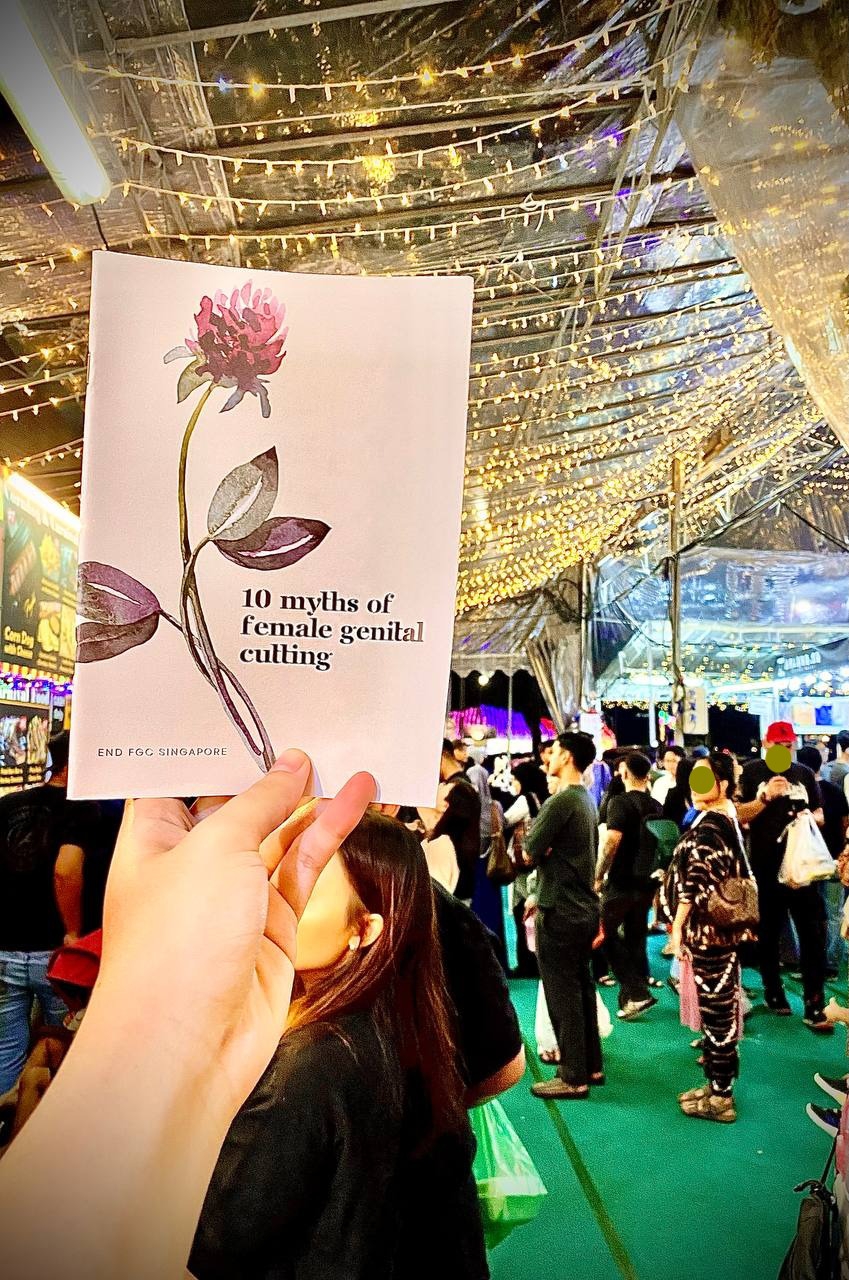

End FGC Singapore uses educational methods to challenge stereotypes surrounding FGC, including discussing how FGC should not be interpreted as a religious mandate for Muslim women. As part of their programs last year, End FGC Singapore decided that during the holy month of Ramadan, they would bring awareness to FGC through hosting a public awareness campaign.

“This isn’t the first time we’re doing this – last year we distributed our booklets outside the mosque, but decided to take it to the next level this year in order to reach out to the people we’re trying to influence.”

The bazaar is set up during Ramdan which consists of food, vendors, and activities for families. Saza reflected on choosing the Bazaar, explaining that it was the event to pass out educational booklets on FGC because “the Bazaar is younger, attracts a larger crowd, and is more hip. It’s important for effective activism to be able to segment our audience and then provide targeted marketing. Those are the people whose minds we are trying to broaden and influence.”

End FGC Singapore sought to speak with the younger generation of Muslims in Singapore because they felt that a younger audience would be more receptive and open minded to criticizing the practice of FGC; focusing on younger Singaporeans also gives End FGC Singapore the opportunity to create generational change. These young people will one day hold positions of power in their communities, and because they have been exposed to End FGC Singapore’s activism, there is a greater chance they may put forward laws and ideas that help end FGC.

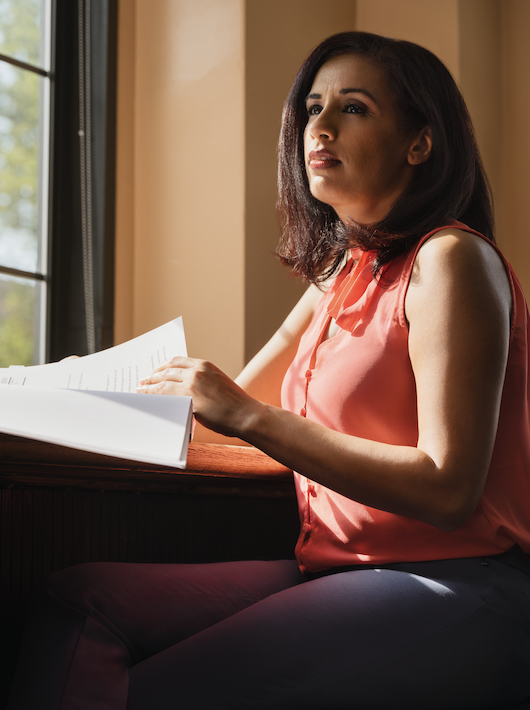

Saza also explored different people reactions when being handed the booklet:

“Common questions that we receive are along the lines of, is this practice required in Islam, is this practice safe if it’s done by a doctor, is sunat perempuan the same as FGM, etc. So we addressed the issue from a health perspective, a religious perspective, and then a cultural perspective.”

End FGC Singapore have set themselves up to provide future activist programs because they have established a common connection within their community. End FGC Singapore also made sure that the information in the booklet was educational, while still appealing to inclusion of the Muslim community.

But in distributing the booklet at the Bazaar, they did run into some challenges. “Most people are quite shocked at first because they don’t expect to talk about FGC in a Bazaar.”

Saza’s work has also gained media attention, as the booklet program was featured in an article published by Mediacorp Today. However, not all the feedback has been positive:

“The Ramadan Bazaar organizers reached out to us after the article came out and messaged me saying that I’m not supposed to do this because I didn’t get approval (in Singapore you need to get approval for everything). However, it is legal to give out any non-political booklets in all public spaces. So we had a meeting with them arguing that the Ramadan Bazaar is a public space.”

Despite the pushback, End FGC Singapore's use of a public space to deliver the booklets is a testament of their commitment to community-based activism. Saza and her team know their community and have tailored their community engagement work towards the youth, who they hope will understand the harms of FGC and work towards prevention of it for future generations. This community-centered approach creates space for dialogue between communities and activist organizations, which is vital to ending the practice of FGC.