The Women Deliver 2023 Conference (WD 2023) is scheduled to take place in-person, as well as virtually, from 17-20 July 2023, in Kigali, Rwanda. The conference is expected to convene 6000 people in Kigali, and over 200,000 people online.

Before the opening ceremony on July 17th, there will be a series of Pre-Conferences held over two days from July 15-16th. Sahiyo is incredibly proud to co-host and be part of the planning of this year’s Pre-conference on FGM/C -Catalyzing Global Action to End FGM/C.

About FGM/C Preconference:

The FGM/C Pre-Conference, Catalyzing Global Action to End FGM/C, will be a space of shared solidarity, bringing together activists and organizations working to end FGM/C across Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Europe, and America. It will promote knowledge exchange, interregional collaboration, and global cooperation with the aim of catalyzing collective action and movement building, designing actionable commitments, and working toward substantive structural change.

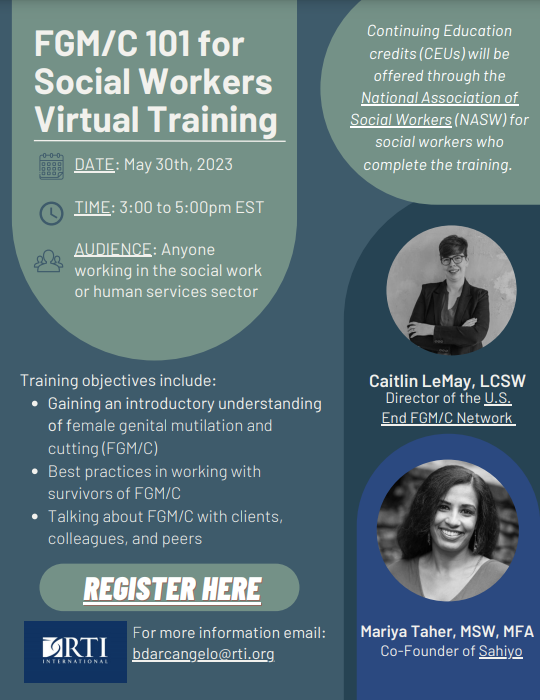

Hosts: The Global Platform to End FGM/C, Orchid Project, ARROW, End FGM European Network, Sahiyo, Equality Now, Amref Health Africa, The Girl Generation, IPPF ARAB World Region, U.S. End FGM/C Network, and End FGM Canada Network

Date and time: July 16, 2023 from 8:30 AM – 5:30 PM CAT

More information: https://www.wd2023.org/pre-conferences

About Women Deliver 2023:

The Women Deliver 2023 Conference, using intersectional feminist principles, will address a wide range of issues impacting girls and women– including (but not limited to) climate change, gender- based violence (GBV) and unpaid care work. The theme of WD2023 is Spaces, Solidarity and Solutions. Learn more about the Conference here.

History of the Global Platform:

At the FGM/C Pre-Conference ahead of Women Deliver 2019 in Vancouver Canada, the organisations that would come to make up the Global Platform for Action to end FGM/C came together in recognition of the imperative for us to work together - as civil society, donors and allies – to make FGM/C a practice of the past. This represented the first time that global FGM/C activists from Africa to Europe, from Australia to Asia and to North America came together to unite voices around a global call to action to end FGM/C. The Asia Network to end FGM/C was also formed during Women Deliver 2019.

The global and regional partnerships that were formed on that occasion have grown and strengthened their internal cooperation, working towards common advocacy goals at the regional and global levels respectively.