(Originally published on Café Dissensus website on May 5, 2016. Republished here with permission from author).

(Trigger Warning: Below is the account of one woman’s experience of her sister undergoing FGC. We thank her for being brave and sharing her story with us).

Country: India

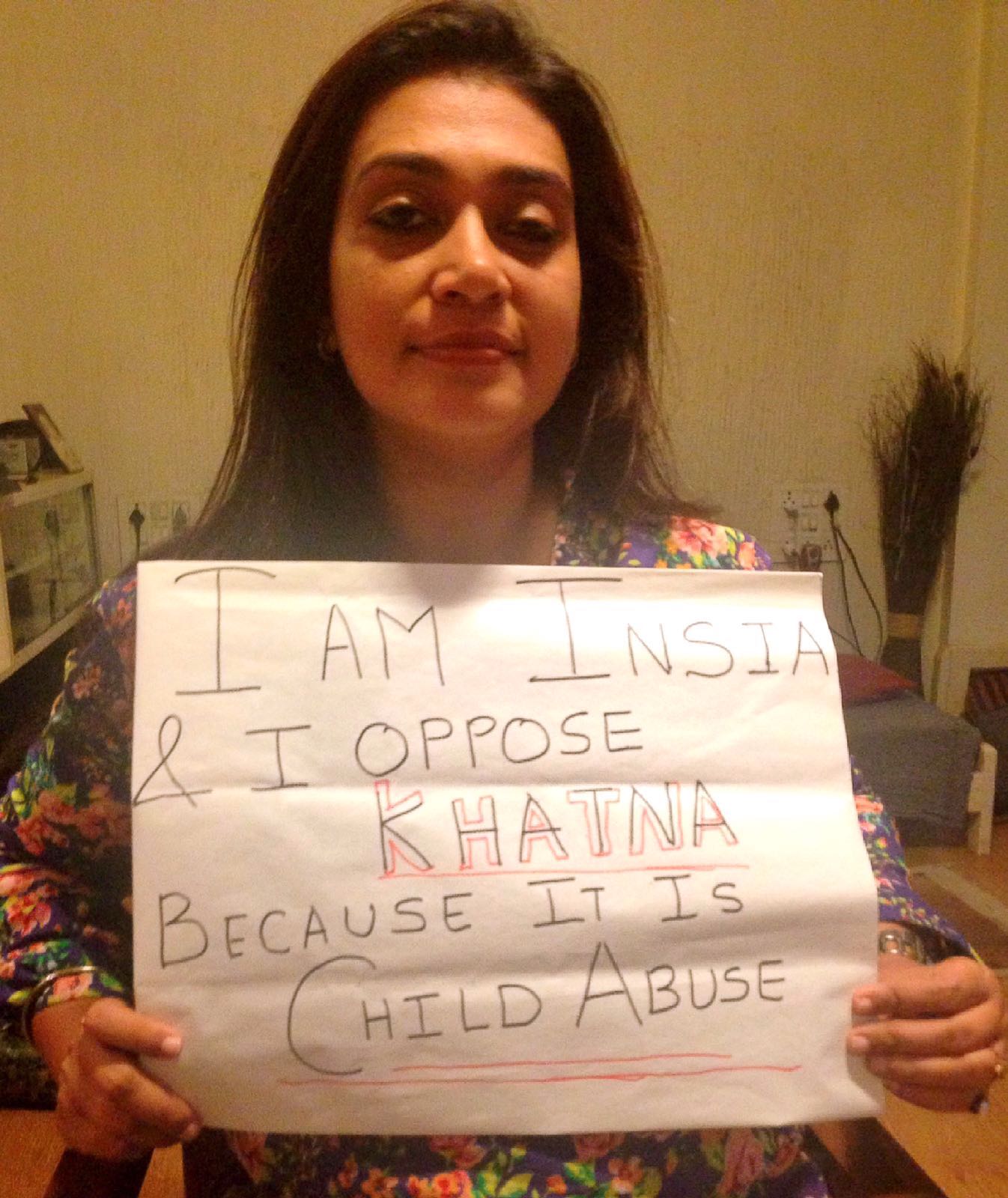

By Insia Dariwala

I still recall that wet rainy day in our four-by-four cramped shoebox. To the world it was a pit – dark and dingy; but to us this was home – a royal home that ceremoniously ended where it began.

In our spare time, my sister and I loved sitting at the windowsill that overlooked years of dirt and misery. Imagining the intertwined pipes that crawled off our chawl to be a game of snakes and ladders, I wondered if we would ever escape the venom of this dreaded place. The narrow and smelly cramped lanes had pain written all over them. Every stain on the walls lining the chawl was a reminder of a dream splattered perhaps by a .32 pistol. Luckily my father’s stains were far more conventional: two betel paan leaves with lots of limestone and kimaam (an intoxicating ingredient).

Each night as we prepared for our descent into the world of dreams, we would be awakened by a loud bang at our door. In his usual drunken state, our neighbor had once again forgotten his house. His constant arrival at our doorstep was a grim reminder of how easy it was to get lost here. Most of the time we lulled ourselves to sleep under a wrinkled, patchy blanket and my sister and I felt more at ease there than anywhere else in the world. It was here that we plotted our future, and re-lived our Cinderella moments of getting rescued by handsome knights in shining armor.

Fatema would joke, “But what if he doesn’t come?”

To which I would widen my big eyes, make a sword from my long braid in one hand and say, “Fear not, my dear sister, I will protect you no matter what.”

Fatema would then giggle loudly, only to be shushed by our mother-hen who was always on the lookout for boys peeping through our broken glass windows.

Our mother-hen was a dutiful wife with an unflinching tolerance for dad’s consistent tyranny. Thanks to my father, our never-ending poverty was sponsored by his alcoholism. His frequent showers of physical and verbal abuse were far more generous than the money he put in her hands.

Almost all of our mornings dawned with mom’s screams and dad’s abuses. That day too was no different, or maybe it was, because this time the shrieks were not just mom’s. Dad hit mom hard across the face. Hurriedly, we ducked behind the tattered curtains, getting our uniforms on and struggling to dodge the gaping holes in the curtains, lest someone should see through our innocence. Looking through those holes, I wondered if my future too would be this hollow.

When the storm settled, we peered into hell. Maa’s eyes were red. Her lip had a bluish tinge and it was hard to tell if it was from the slap she must have got or from biting down her urge to retaliate. Pappa nonchalantly spat his venom out of the window and looked at us with disgust.

We then sat down to eat our breakfast, hoping we would not lose our only meal of the day to the joint family system. The daily bread of salt from my tears was getting quite tasteless now.

Just then Rukaiya aunty walked in, surprisingly, far more pleasant than usual. Mom watched her offer some candy to Fatema. Hopeful and hungry, I put out my hand for one. Instead, she just walked away, leaving me salivating at the candy in Fatema’s mouth. Poor Fatema felt horrible seeing me in tears, but not as horrible as she was going to feel later on.

Mom asked us to run off to school but no sooner had we reached the door aunty called out to Fatema. “Look, Fatema.”

Fatema’s angelic face lit up with excitement as she saw her dream flutter in aunty’s hand. Two tickets to the matinee show of the hit film, Sholay. Fatema always had a weakness for Hindi films and Hindi songs. Even at the tender age of seven, she could sing every song with more proficiency than our older cousins. Had there been an Indian Idol then, she would have surely won. On one occasion, Fatema had come storming into the house, waving a ten-rupee note that the uncles had given her. ‘Golden voice’, they used to call her. We listed hundreds of ways to spend those ten rupees. It’s incredible the things you can do with ten rupees, when that’s all you have. Chandu’s sandwich was first on the list; watching the much awaited Sholay, second. Children below eleven were free, so we could treat our mother to a film as well as the sandwich. After all, she did eat more salt than us. But while our taste buds danced to the thought of Chandu’s chutney, and Mom dreamt of styling her hair like Hema Malini, Dad had already reached into our hopes and vanished with the money. Some other golden voice must have got lucky that night. So on that day when Fatema’s dream of watching Sholay was finally coming true, I too joined in the excitement and begged Aunty to take me along. My pleas, though, fell on deaf ears. They don’t love me as much, I thought.

The tantrums and pleas continued. Fatema looked towards Maa, who kept giving us the look, which meant business. But Dad’s voice overpowered her.

“Let her go. Study is useless anyway.”

Mom reluctantly gave in. Fatema shrieked with joy. I fumed with jealousy.

That’s so unfair, I thought. I reached for my school bag and Fatema looked at me guiltily. Our poverty had always taught us to share everything. Unfortunately, what she came back with that day was something I could never share.

Hours passed. I came back from school, anxiously waiting for my sister. Mom, too, was getting restless. Suddenly the door opened. For some strange reason, Rukaiya aunty was carrying my sister in her arms. Fatema’s excitement was replaced with a deathly paleness. Rukaiya aunty put her down and handed over Fatema’s bloodied underwear to my confused and shocked mother. She ran to Fatema screaming, “What happened baby?” Fatema was in a state of shock. Mom reached to hug her. She winced in pain, trembling like a leaf. Her body was burning up. Mom lifted Fatema’s dress and found blood-stains on her leg. She moved her aside and lunged at my aunt, roaring, “What did you do to my baby? You horrible woman, what did you do?”

My aunt was unremorseful. “Keep your voice down and stop this drama. Every girl in our Bohri community has to go through this. I too went through it, when I was seven. It’s God’s will and a woman’s fate. She is clean now. Just wash her up and she will be fine.”

Mom broke down, helplessly looking at Fatema. “My poor baby, I am so sorry. I don’t even know what these butchers have done to you.”

Wash her up even though she is clean? Every girl’s fate? What was Aunty talking about? The suspense was driving me crazy and my tiny head could not take in the events around me. All I could see was that my beloved sister was crying in pain. Her pretty pink dress had stains of blood. She must have fallen, I thought. I ran in and brought out our blanket, tucking both of us under it. Whatever it was, this magical blanket would surely make it go away.

Years passed. I never met every girl’s fate or became clean but I always wondered what it was. Like every other family, we too wore the garb of denial and went on with our lives. From that day onwards, though, things just changed, even Fatema. I was no more a part of her gang. No more blanket games. Since that day, she stopped sleeping under it. So I tucked it away, along with all my memories of that day.

As we matured, small girlie functions in the family took place without me. Fatema would come home from these functions, with henna on one hand and gifts in the other. My hands meanwhile would be full of thousands of reasons for not having those gifts. They don’t love me as much. Maybe I am not pretty enough. Maybe only one child can participate. She is older than me. Maybe next time I will go. Maybe I have to be a good girl and then I would get to go. Maybe she is the preferred one. My list of reasons, along with my self-esteem, was running out.

Life has moved on quickly since then. We took different roads and have done well for ourselves, leaving childhood scars behind. At least, that’s what I thought, until one day, a sleepover turned into my worst nightmare. Fatema was visiting and stayed with me. We spent hours talking about our lives and in my excitement I pulled out our good ol' blanket. Fatema went pale when she saw it. Tears trickled down her face. I was confused. Surely the blanket could not have been that bad.

“I am sorry. I’ll put it back,” I said.

“Wait,” she said. “Bring it here please.”

Hesitating, I gave it to her. She put it over her body, tears gushing. She looked at me and said, “Remember how you wanted me to tell you the Sholay story? Well, I would like to tell you today.” I was about to tell her that I had already seen it, but she started anyway.

April 14th 1977. On my way to what I thought was a theatre, I saw the film unfold in my head. But I was led to a small dark room in one of the dingy by-lanes of Mumbai, where four women were waiting for us. I was asked to lie down on a dirty bed. I kept asking why. No one answered. I resisted, but my panty was pulled off. My legs were spread apart. Something cold was then applied between my legs. One of the ladies pulled out a sharp instrument and cut me down there. I screamed in agony, but was no match for those women. They held me down tight. It felt like I was going to pass out with the pain. The process was quick for them, but an eternity for me. The women then asked me to keep my legs apart as they left the room. I felt something warm engulfing me from the waist down. It was blood; lots of it. That burning and painful sensation between my groin is something I will never forget. I felt betrayed and humiliated. Locked in that dark room I wondered how aunty could be so cruel. After a couple of hours when aunty returned to check on me she explained how every good Bohra girl has to go through this to become clean. For years I have lived in regret for choosing Sholay over mom’s warnings. Life changed completely after that day. Trust was hard to come by. Not even with my husband. It took him a long time to assure me that when he touched me there, it was not to cut me. Dreams were replaced by nightmares. I lived in fear every day after that day. Every dark place took me to that dark room. The day this happened, I just felt pain, unbearable pain. But today I just feel loss. Every time I bathe, I try to locate that missing piece. I wish it would grow back. I wish I could become a complete woman once again.

Her words trailed off as I touched my own body in the dark. Her pain had traveled to my groin. My tears rolled down my lips and into my mouth. This time, the salt tasted different. Not poor like it used to be, but blood, oozing out of a wound dried up a long time ago. Struggling to breathe, I tried hard to reach out for words that would make sense. But like Aunty, they too had betrayed me. Fatema was silent, and her body was as calm as on that dreadful day. I was trembling. The blanket had failed me this time. For years it had always been our shelter, our safety zone. No one could trespass here. It was our world and I was the protector. But this time, as I watched Fatema curled up next to me like that little girl of years ago, I realized I had not kept my promise. I had failed to protect her. Full of guilt, I lay down beside her, trying to make sense of the endless pain that tradition had put Fatema through, of the blade that had managed to miss my body, but had succeeded in slicing away my soul.

Bio:

Insia Dariwala is an Advertising and Mass Communications graduate from New York and an award-winning filmmaker and child activist. She campaigns against child sexual abuse and female genital mutilation.