Research Summary & Implications

Background

Sahiyo is dedicated to ending Female Genital Cutting (FGC) in the Bohra community, a small global Shia Muslim community. Sahiyo focuses its efforts on public education about the prevalence and impact of FGC, community outreach initiatives, and supporting survivors and activists, with the ultimate goal of driving positive social change around gender violence. Sahiyo recently partnered with a healthcare market research consultancy to conduct primary market research with activists speaking out against FGC, in an effort to better understand activists’ challenges and hopes for the future.

In this article, we hope not only to summarize the key findings from our primary research and draw implications for the broader gender violence activist community, but also to underscore the importance of conducting primary research with activists.

Research Methodology

Research entailed two phases: first, a quantitative, online survey was sent to anti-FGC activists across the globe. Second, follow-up interviews were conducted with activists from the online survey sample, who expressed their willingness to further participate in the research.

Sample & Demographics

All activists who took part in this research grew up in the Dawoodi Bohra religious tradition, and are now self-described as active in speaking out against FGC (‘khatna’).

Phase 1 Quantitative Sample:

- Between 40-50* activists took the online survey, 91% of whom were female.

- Activists’ ages varied, though 56% were under the age of 35.

- The majority (~3/4) of activists reside in either the United States or India and were highly educated, with 96% having at least some graduate degree.

- Although respondents were raised Dawoodi Bohra, only 43% still identify as Dawoodi Bohra, while 37% are non-practicing. However, 67% of respondents socialize with Dawoodi Bohras at least sometimes (every couple of weeks).

- 69% of respondents personally underwent FGC, while 94% had a mother who was cut.

Phase 2 Qualitative Sample: 7 activists were interviewed in follow-up telephone conversations. These 7 activists had variable ages, countries of residence, and genders.

Key Findings

Although each activist’s story is unique, they all shared the drive to end FGC in their community and more broadly. Their activist journey typically started with a realization about the prevalence of the practice: whether this be through a family member speaking out, a documentary, or media coverage; the realization sparked further investigation. Although some activists had memories of their own experience of being cut, many did not. For the latter individuals, the realization as adults about the practice’s prevalence occasionally came with a realization that they too had been cut, triggering an intense emotional response. For all activists, the initial anger and shame upon learning of the practice’s prevalence often led them to ask family and friends about FGC in their community, but they were met with a culture of secrecy and silence. Even when activists did open conversations with family and friends, they found the practice was often justified as a longstanding tradition, necessitated by religion.

This culture of secrecy and acceptance, paired with painful body or narrative memories of their own cutting, were said to be key drivers to speaking out. Many activists feel that not only does FGC have long-term physical and psychological health impacts, but that it is also a form of child sexual assault and/or abuse given the lack of consent. Furthermore, activists acknowledge that FGC’s underlying misogynistic and patriarchal factors make it part of a larger movement to control women. In short, activists feel that FGC does only harm with no benefit and must therefore be ended.

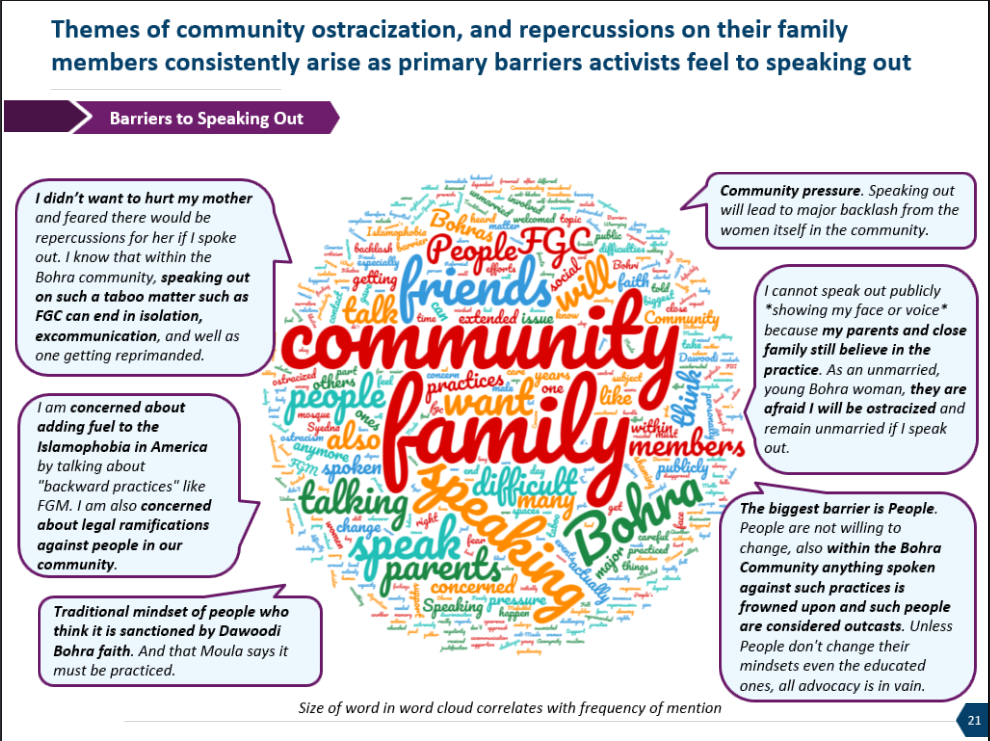

Challenges to speaking out:

Overlap of religion and community

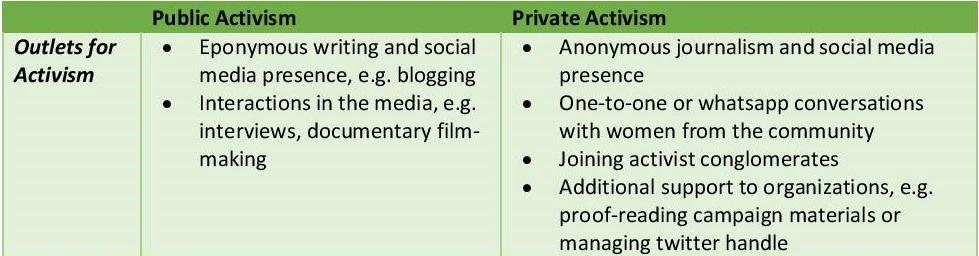

The most significant challenges activists face when speaking out stems from the high degree of overlap between religion and community in the Bohra community. Although most activists are fairly open with their families and friends about their activism, they feel only moderately supported by their loved ones, largely due to concerns with the activism’s social repercussions. These concerns are linked to the social characteristics of the Bohra community, which include long-standing traditions of loyalty and closeness, in which the religious community often dictates social circles, romantic partners, neighborhood housing, cemetery sites, and more. This overlap causes speaking out against FGC to be seen as an attack on the community and faith at large. As a result, activists fear that speaking out would lead to discontinued social and professional bonds and ceasing of access to religious privileges. For some, these potential social repercussions bar them from speaking out publicly, so they pursue more private means of activism, such as anonymous writing and supporting organizations like Sahiyo.

Religious authority

Concerns with speaking out are further driven by the authority of the Bohra religious leaders. Considering that there is no clear religious justification for FGC, its continuation relies upon the leaders’ mandates and interpretations. Questioning of the religious leaders is deeply discouraged and potentially dangerous—causing many activists to not only fear speaking out, but also sometimes demotivating them, making them feel that without the support of religious leaders, their activism is a ‘lost cause.’

Considering the challenges above, many activists feel torn between wanting to end the practice and wanting to maintain a close connection to their faith and/or community. Even activists who are no longer involved in the Bohra community still fear risking the social wellbeing of their loved ones. Activists present this as a ‘catch-22’: loyal Bohra members are well respected by their community; however, speaking out against a taboo practice might oust them from it, rendering their authority no longer valid.

Conversation challenges

When activists do speak out publicly or privately, they find the conversation about FGC particularly challenging. The lack of robust, publicly available information about the practice’s prevalence in the Bohra community, as well as about its physical and mental consequences on the girls’ health often result in other Bohra members undermining the impact of khatna. Many community members present khatna as ‘not as bad as other types of FGC’. These arguments are particularly difficult for activists who do not have a clear memory of their own experience or believe that it has not had a negative impact on their life. They therefore risk feeling further invalidated and oftentimes doubt themselves. These factors, paired with the importance laid on tradition and religious authority, poses a serious difficulty for the activists in communicating the need for open conversation about FGC eradication.

Islamophobia

Lastly, the challenges faced are not limited to considerations within the Bohra community. Some activists in America fear that public attention to FGC in a Muslim community might fuel pre-existing islamophobia, ultimately risking the wellbeing of their community. Additionally, given that the practice is illegal in many of the countries of active Bohra communities, some activists fear legal repercussions for people in their family, who they tend to also see as victims of the practice’s broader normalization.

Hopes for the Future:

Activists acknowledge that the unique social and religious considerations surrounding FGC make alleviating many of their challenges difficult. However, they hope that with continued conversation and increasing public awareness more people will learn about and, eventually, question the practice. Many activists feel that every conversation matters, even just 1:1 conversations with loved ones: each person who chooses not to cut their child is ultimately making broader change. They hope that personal stories are shared by name and anonymously, with the facilitation of active support groups, which allow a safe space for women to discuss, ask, and learn. Additionally, crucial information about FGC in the Bohra community and about its overall impact on women’s health and position in the society is expected to provide useful tools to activists and new opportunities for community discussion. Considerate presentations about the practice by the media will further support this dialogue. Although they acknowledge that broader, more formal change spearheaded by religious leaders is unlikely in the near future, community-level change is both possible and valuable. Through a combination of both public and private activism, activists hope that they can continue to build compelling arguments against FGC as they spread awareness.

Implications & Conclusion

Implications on FGC activism

Resources that reinforce the argument for eradicating FGC would significantly support FGC activists: information on the prevalence of FGC, research on the physical and mental health impacts of Type 1 FGC, useful guidance on legal repercussions of publicly sharing experiences and on arguments concerning child sexual abuse and gender violence, and religious arguments against the requirement of FGC for the Muslim tradition. Additionally, activists acknowledge the need for resources on how to strike a balance between empathy and understanding and anger and frustration in a conversation about FGC, especially with active members of the community, who might feel threatened or offended by activists. Activists require such guidance so that they can effectively encourage women to share their experiences and both women and men to listen and learn about FGC.

Implications on research methodologies

This study evidences the critical nature of conducting research directly with activists to better understand their needs. The use of both quantitative and qualitative primary research techniques facilitated both breadth and depth in the findings, therefore increasing existing evidence about FGC prevalence in the Bohra community and activists’ greatest challenges. These findings are crucial in drawing attention to FGC within and outside the community, especially considering the secretive nature of the practice: such evidence can empower activists, who are often met with doubt about their cause. Discussing directly with some of those activists about their own experience and the impact of their activism contributed to further understanding the reasons behind their worries and identifying ways to overcome the challenges. We believe that such methodology can be a robust way for any activist organization to increase evidence, draw attention, and help their members.

Implications on broader gender violence activism

Although the religious and social considerations are certainly unique to the Bohra community, many of the concerns expressed by these anti-FGC activists were resonant of concerns from people speaking out against any form of gender violence: concerns about social repercussions against themselves or their family. Although these repercussions orient more around the close-knit nature of the Bohra community, the underlying anxieties exist for any form of anti-gender violence activist: fear of potential discrimination in the workplace, isolation from family/friends, etc. The fear of negatively impacting one’s community prevalent among anti-FGC activists could be analogized to the fear of negatively impacting loved ones seen in many forms of anti-gender violence activism that results from the perpetrator of the violence often being part of one’s own immediate social circle. We believe that research, like the presented one, which allows gender violence victims and activists to voice their worries of speaking out, especially in terms of the activism’s immediate impact on their life, is crucial in order for organizations, like Sahiyo, to understand how these victims and activists can be best supported.

To view this report as a PDF, click here.

If you are interested in learning more about this study, its results, and their impact for FGC activism, please see the attached presentation, which includes detailed findings and implications.