By Debangana Chatterjee

Though the exact reason for the origin of Female Genital Cutting (FGC) is unknown due to the dearth of conclusive evidences, multiple theories revolve around how the practice began. FGC precedes both the start of Islam and Christianity and is practised predominantly because of cultural traditions. FGC is not limited to a single community, religion or ethnicity. Rosemarie Skaine mentions that there are archival documentations indicating a Greek papyrus to have recorded women to get circumcised while receiving dowries around approximately 163 BC. In fact, there are several Greek scholars mentioning its prevalence before the advent of Christianity.

Broadly, the practice is believed to have originated in Egypt where circumcised and infibulated mummies were found according to Frank P. Hosken. Gradually, it spread around the contiguous areas of the Red Sea coast among the tribes through the Arabian traders. In Hanny Lightfoot-Klein’s opinion, though the practice is believed to first have spread in the form of infibulation, clitoridectomy increasingly became the more acceptable form of FGC. During the Pharaonic era, the Egyptians believed in gods having bisexual features. Elizabeth Boyle recounts that these features were believed to reflect upon the mortals, with women’s clitoris representing the masculine soul and men’s prepuce that of the feminine soul. Thus, circumcision was considered to be a marker of womanhood and a way to detach from her masculine soul. As it became a socio-cultural norm, FGC became the utmost criteria for women’s marriage, inheritance of property and social acceptance in ancient Egypt.

Lightfoot-Klein also suggests that population control was also one of the driving forces behind the practice as by controlling a woman’s sexuality; it kept the woman’s desires in check and made her sexually modest. Due to the narrowing of the vaginal orifice through infibulation, women would experience excruciating pain during sexual intercourse and thus, it becomes an effective measure to hinder premarital sex among women and ensure their fidelity. In fact, in places like Darfur, sudden desertification of arable lands made infibulation one of the population control measures.

Boyle suggests the Egyptian practice of FGC and slavery can be correlated for providing an explanation of its origin. Before the advent of Islam, Egyptian rulers expanded their kingdom towards the southern region in search for slaves. As a result, Sudanic slaves were taken to Egypt and the areas nearby. Incidentally, slavery became commonplace with its aim to deliver servants and concubines to the Arabic world. As a result, women with stitched vaginas were in high demand due to the lessening possibilities that they would become impregnated.

But after the arrival of Islam in the region, a strict prohibition towards enslaving other Muslims allowed the practice to get extended to other parts of Africa when the slave traders introduced infibulation among the non-Muslims to raise women’s value as slaves. This not only explains the introduction of FGC among North-African communities, but also explicates the coincidence of its spread in Africa simultaneous to the rise of Islam. In some cases, the practice has also sought its validation through Islamic scriptures. Doraine Lambelet Coleman says that one of the hadiths in Islam is thought to permit a limited form of cutting, though the hadith is also contested for being deficient of its genealogical authenticity. Despite the Prophet being explicit about sunna (tradition) on male genitals, FGC’s existence within Islam remains debatable. The practice was believed to be introduced in the South East Asian countries at around approximately 13th century, supposedly due to the reasons of Islamic conversion process after the change in regime. The predominant Shafi school of Sunni Islam in Indonesia and Malaysia justifies FGC as an Islamic practice and is culturally influenced by the Eastern part of the Arabian peninsula, the region where presently Yemen and Oman are situated. The justification for the practice in these countries come as they prescribe ‘nicking’ of the outer clitoral skin without really injuring the female genitals. In fact, this explains the burgeoning medicalisation of the practice in these two countries. In Singapore, the practice prevails due to the regional influence of Shafi Islam on the one hand and a few practicing ethnic Malay population on the other. The practice is rife among the Kuria, Kikiyu, Masai and Pokot people in Kenya, Zaramos in Tanzania, Dogon and Bambara people in Mali to name a few. Scholars have also indicated the income-generating facet of the practice in the face of unavailability of alternative livelihoods for the individual circumcisers.

Though immigration due to slave exportation and other reasons is considered to be one of the predominant forces behind the spread of FGC in the West, L. Amede Obiora claims it was also reportedly performed on western women, especially in the United States, even in the 1950s as a cure to ‘unnatural female sexual behaviour’ that ranges from homosexuality, female masturbation to depression. References to ‘genital altercations’ in the Western countries are also not unfamiliar. In fact, Obiora also mentions that there are accounts of an English gynaecologist Isaac Baker Brown expressing his clear endorsement of such altercations in the early 1800s.

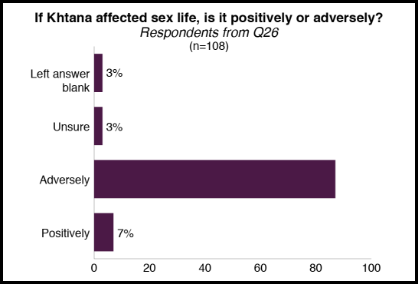

To talk about India, the practice is prevalent among the Bohra community who came to the Western part of India from the North-African region as a trading community. The defenders of the practice in the community justify this as a stand-alone practice of khatna which, unlike other grave forms of it, only comes to denote removal of a pinch of clitoral skin bereft of its harmful effects. In this regard, often local circumcisers are being replaced by the medical professionals to highlight the hygienic conditions of its performance and gain greater legitimacy in its favour.

On a whole, the practice has transformed and evolved dynamically since its origin. FGC through the course of its evolution came up with multiple facets and spread across cultures and geographic regions with various manifestations, meanings and narratives being attached to it. Tracing its origins, thus, not only helps in understanding its nuances but also minimises the tendency towards its homogenisation.

More about Debangana:

Debangana is a doctoral scholar at the Centre for International Politics Organisation and Disarmament (CIPOD), Jawaharlal Nehru University. Through her research, she is trying to locate the existing Indian discourse surrounding the practices of FGM/C and Hijab into the frame of international politics. If you would like to connect with Debangana, you can reach her at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..