***

Having experienced khatna at a young age, I know firsthand the tremendous toll that a community’s traditions can have on the women and men who live according to them. What follows is my story and the story of six women interviewed for my thesis, who live in the United States and underwent khatna. The women ranged in age from 22 to 59 years, were born or spent the majority of their lives in the United States, and have some amount of higher education. They all experienced khatna between the ages of 5 to 7 years.

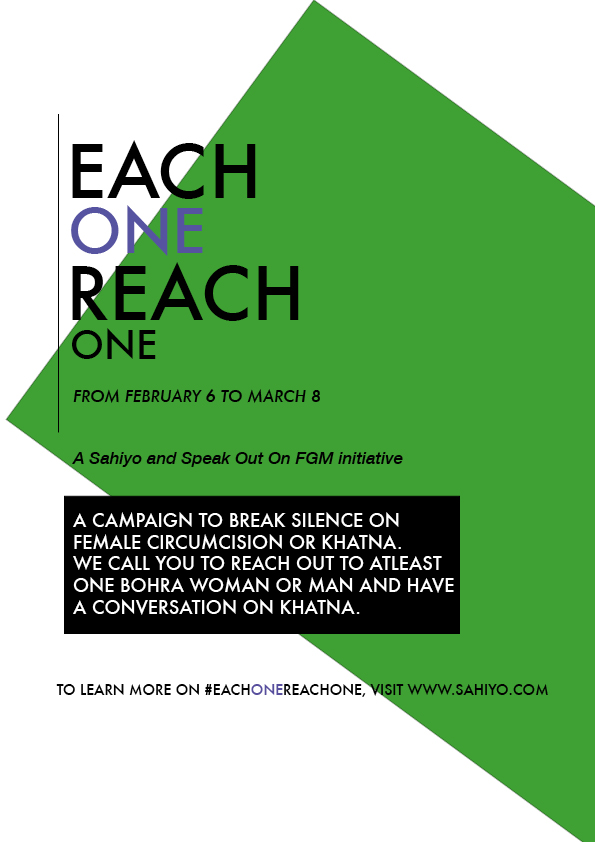

By interweaving their voices with my own khatna experience, I hope to show the wide spectrum of emotions and experiences involved in such a complicated practice. Most importantly, I hope to break the isolated feeling, the unspoken taboo surrounding FGC. We are not alone. FGC is a shared experience by many women, bound by tradition, living today.

“When men are oppressed, it’s a tragedy. When women are oppressed, it’s tradition.”

~ Letty Cottin Pogrebin

Female Genital Cutting (FGC). Some refer to it as Female Circumcision; others call it Female Genital Mutilation. As a child, I knew it as khatna. No matter the name, it is the process of removing part or all of the female genitalia. Within the Dawoodi Bohra religious community, a ritual performed on girls. I never knew it violated the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, let alone was a practice criminalized in the United States by the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996.

According to the United Nation’s Children Fund, more than 125 million girls and women alive today have been cut in Africa and the Middle East. As many as 30 million girls are at risk of being cut over the next decade. [i] Within the United States, the Center for Disease Control, found that in 1990 an estimated 168,000 girls and women were living with or at risk for FGC. In 2000, it was found that an estimated 228,000 women had undergone the procedure or were at risk, resulting in a 35% increase from 1990. [ii]

The practice is categorized as violence against women, yet the community I was raised in, often praising themselves for emphasizing women’s education, practiced it. In graduate school, for my thesis, I sought to answer the question of why FGC continued in this day and age.

Upon initial research, I found, to my dismay, that reports on FGC within the United States, only included immigrant women from African countries where the practices was widely known to occur. Excluded from statistics were women like me, born in the United States, growing up in a community whose origins were from Asia and knew FGC to be an important tradition. Further, few qualitative studies, depicting the stories of women, American women, who had knowledge of the practice within this country existed. Here then is my story and the story of six women interviewed for my thesis, who live in the United States and underwent khatna. [iii]

I found, to my dismay, that few qualitative studies, depicting the stories of women, American women, who had knowledge of the practice within this country existed.

These women shared their experiences due to a promise of anonymity. They had to. They did not want loved ones – those who performed khatna or allowed their daughter to undergo it, getting in legal trouble. Within the United States, consequences of contributing to FGC can result in removal of child custody, prison time and/or deportation. [iv]

The Khatna Stories

Note: quotes from interviews are italicized

The summer before I began second-grade, my family visited relatives in India. One morning, my mother and aunt took me to an apartment inside a run-down building located in Bhindi Bazaar, a Dawoodi Bohra populated neighborhood in south Mumbai. Inside the apartment, several elderly ladies dressed in saris greeted us. Initially there was laughter and much chatter. Then I was asked to lie on the bare floor. The frilly dress I wore was pulled up to reveal my midriff and my underwear pulled down, revealing parts I had been taught were to remain private. I couldn’t see what it was, but something sharp cut me and I began crying out in pain.

You’re given a pain injection, pain medication, to numb the area and the piece of skin that’s removed is not even a centimeter, not even a millimeter it’s so tiny.

Once the procedure was complete, my mother embraced me and the elderly ladies, trying to be friendly, handed me a soft drink called Thumbs-Up to chase away tears streaming down my face. We then left the dilapidated building and I hid the memory from my conscious for the next several years.

As a teenager I learned what happened was Type 1 FGC, where all or part of the clitoral hood is removed, sometimes along with the clitoris. But this image is not brought to people’s minds with FGC is mentioned. Instead, Type III or infibulation, the most severe form, involving removal of all or part of the external genitalia, is the form garnering the most attention. Leaving Type 1 to be understudied.

People try to generalize the practice. They put it in a box, so when you think of FGM you think of tribal communities in Africa. African girls getting sewn up and glass bottles and shards of glass cutting them and you think of the worse, you think of the extreme.

After learning khatna violated human rights, I became angry with the Dawoodi Bohras and for a few years, I emotionally struggled with what had been done to me. I also wondered if khatna had negatively impaired my sexual abilities. Gynecologist today cannot distinguish any genitalia differences, perhaps there were no adverse effects. I do not know. But I alone did not have this fear:

I was scared because my mom always talks about how she hates sex and it’s the worst thing God ever created. It’s probably because she doesn’t fucking enjoy it. Geez, no wonder because who knows how much of her clitoris is gone.

Yet since learning what happened to me, I never once grew angry at my mother. She was doing what she believed was necessary for me to be a good Dawoodi Bohra girl. My mother was only following the traditions she had been raised with:

My mother told me she’d been approached by a woman in the community, an elder like the priest’s wife and she told my mother it was time for me to get it done. And my mom didn’t question it because she felt it was something that we all had to do. And she herself had done it and her mother before her had been cut.

And tradition is a hard beast to slay, if the practice becomes normalized, common, like getting your period:

It was something we all knew we had to get done at that age [7]…It’s like when you get your period…if other people have gotten it then it’s just a rite of passage and you’re ok.

Like any tradition, to those with family and friends who underwent the same procedure, and to see them come out okay, the fear and uncertainty of the unknown is taken away. But for others, there is an emotionally scarring that cannot be erased.

I felt violated. I felt it was a situation completely out of my control. I went through everything you go through in a trauma- although it happened many years before. I went through that trauma at 19 and it lasted for years. I was depressed. I was acting out.

Some suffered. Some did not. There had to be a reason why this centuries old practice was continued generations after generation. I learned of many reasons:

I don’t know if it’s a definition of being Muslim or if it’s one of the criteria for having to become Muslim, but it is a pretty important factor when people convert to Islam they have to get this done…I mean not just for an external appearance or for society to know it has been done. I mean not for that reason alone, but it somehow affects your mind and body and that change is necessary for you to become Muslim. In that regard I would get it done, but to be honest I would just continue it because of the tradition.

I’ve asked around as to why it has been [performed] and I’ve gotten different answers like some of it’s just been for religious purposes, but our bhen sahab (religious clergy’s wife) told us it enhances your sexual experience but I’ve heard otherwise. I think it’s more done because they’ve been following it for many years and they don’t stray from tradition.

Tradition constitutes the transmission of customs or beliefs between generations. Tradition was the overarching theme for continuing khatna among Dawoodi Bohras. The practice was believed to connect women to their culture and for those who agreed with the practice, it was part of their identity. Even when communities crossed oceans to establish new lives elsewhere, this tradition continued, providing a sense of comfort often lacking in an alien world.

I found through observation that people within the United States overcompensate for the fact they’re not living in India and far from their homeland. So they really make sure they stay within the culture that they know, so for that reason I feel they probably practice it more than people in India who have probably left the practice because they’re around that community all the time and people here it’s like we don’t want to lose that culture, we don’t want our kids to lose that culture, so they abide by every single rule more so.

The need to hold on to culture is a strong pull within this community, perhaps more so in the United States, where the ideals and values often feel contradictory to those in the homeland.

I think it’s still done by a lot of our immigrant parents to their children here because of the western temptation and sex and partying and all of these things that their children are exposed to…that might not normally happened in India or Africa.

Not all agree with the practice. Yet, speaking against it comes with consequences.

I didn’t want to [speak up and] make it bad for my parents because all they have is this community and they want to be a part of it and they choose to be a part of it. I don’t identify with it but it’s all they have. They’re here. They’re immigrants from another country. They’re not going to find people like them anywhere else. They need that and now they’re old and they want it even more.

She continues to explain:

It’s the social ostracism that people are worried about. Not belonging and the gossiping and the reputation trashing.

The need to belong, to feel socially accepted, a universal feeling, can prevent those who would oppose FGC from speaking, feeling they would be in the minority and not wanting to be socially excluded.

I shared the khatna stories, not so that any of us can be viewed as victims of an intolerable act, but to illustrate FGC is a complicated custom. It cannot simply be considered an act continued by ignorant people, the reasons given for its’ continuation have been rationalized and been given cultural or religious significance. My wish is not to disgrace this community but to demonstrate the role tradition plays in continuing a practice oppressive to women. Khatna is considered a private matter, not one to be discussed openly. Yet, that is the first step towards bringing an end to this centuries old practice imposing violence on women. Let the conversation continue.

***

[i] Retrieved June 30, 2014, from UNICEF: http://just2050.temp.domains/~sahiyoor/images/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf

[iv]

Legislation on Female Genital Mutilation in the United States. (2004, November). Retrieved March 20, 2009, from Center For Reproductive Rights:

www.reproductiverights.org