by: Anonymous

Age: 30

Country: United States

I first learned that khatna had been performed on me when I was 11 years old. My mother told me, and even then the hair on my neck rose and I had a clear instinct that what had happened wasn’t right. I asked my mother why Bohra girls were cut when there was no evidence that it had the same benefits as male circumcision. She responded with the familiar refrain: hygiene, marital bliss.

At that time, I had no idea what a clitoris was supposed to look like. My mother described it to me, never using that word, but saying that it was a “long thread of flesh” that hung out of the vaginal hood. It had to be cut because it would otherwise rub constantly against my underwear. For the Potterheads out there, the image that sprang to my mind was of an Extendable Ear in my panties, a long flesh-colored string that had to be snipped to curb continuous arousal. I had never seen a picture of a clitoris, nor could I. I’d grown up in a country where the Internet was heavily censored and the chapter on reproduction was ripped out of our Biology textbooks. That image of the clitoris as a long flesh-colored string stayed with me until I looked at cartoon pornography as a teenager in the United States. But let me be clear, because this detail about my education is a gateway to Orientalism: I had an excellent primary education, and I was far better prepared for graduate school than many of my US-educated peers. The fact that schools in that region refused to include human reproduction in the curriculum was shortsighted and foolish, but not unlike the abstinence-only curriculum I’ve learned about since moving to the US.

But let me return to that moment my mother told me I’d been cut: since it never crossed my mind that I would or could be sexually active before marriage, I only thought about khatna once or twice a year until I was married. And that’s when I realized that sexual intercourse was extraordinarily difficult for me. My vagina would convulse, and even the thought of using a tampon triggered these convulsions. My condition went undiagnosed until years later when my OB/GYN attempted to do a pelvic exam. She had no warning because I did not tell her about my difficulty with intercourse. Peering over the stirrups, she apologized for causing me pain, and asked me to breathe deeply while apologizing rapidly: “Just one finger, I’m sorry I’m sorry I’m so sorry almost done almost done, and relax.” I learned that I had vaginismus, and needed physical therapy.

As I talked through my condition with my wonderful doctor, I learned that an early childhood trauma was likely the cause for my vaginismus. The symptoms pointed towards a psychological trigger rather than physical limitations, and the more I reflected on my condition the clearer it became that I had always been unable to tolerate even the idea of penetration from around the age khatna had happened to me. Any kind of insertion seemed laughable to me as a teenager, whether I was washing myself in the shower or attempting to masturbate. This points to the idea that women who don’t consider themselves victims – and I certainly didn’t and don’t – can experience long-term effects of khatna that we may not even (or ever) be aware of.

When I eventually saw a picture of a healthy and anatomically accurate clitoris for the first time, what I’d already suspected was confirmed: there was no hygiene-related reason to snip it, and far from enhancing my “marital bliss” it had all but devastated it.

But learning about khatna revealed something about me to myself: even as a child, I recognized the value of empirical research when it came to making decisions about altering bodies – particularly female bodies, which have historically always been more vulnerable. Even as an 11-year-old, I knew the benefits of male circumcision – I had just learned about trench warfare during World War II, and the infections that raged among uncircumcised men living in those filthy conditions. And as I reflect on that moment when I was 11, it makes perfect sense to me that I chose a career in research.

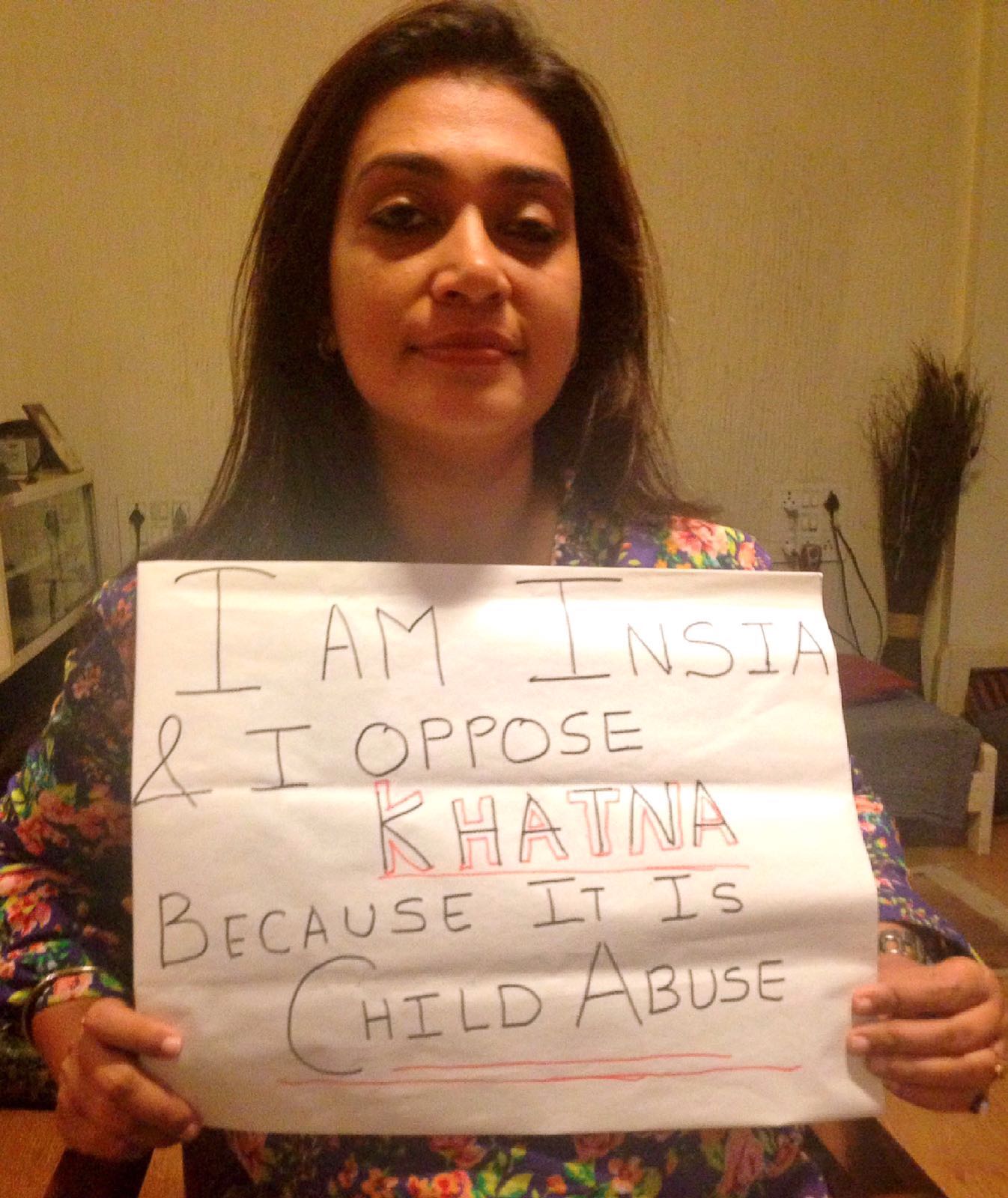

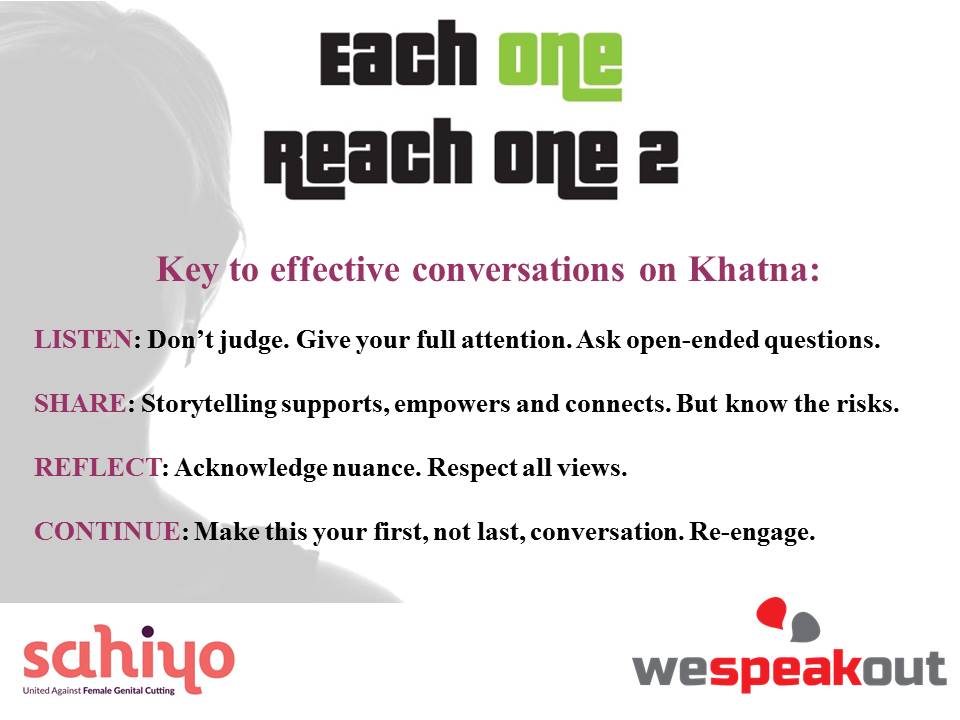

Another thing I recognized is that not only is the term “victim” disempowering when referring to women who have experienced khatna, but also entirely inaccurate. Activists have argued against the term “victim” for decades, particularly when it comes to describing women and gender-queer survivors of physical abuse. However, the term is misleading too. It is an easy label assigned by the status quo, and a particularly effective way for those in power to demonstrate their investment in “women’s issues.” It is a gateway to continued imperialism, where the narratives of marginalized groups are stripped of nuance, or hidden entirely.

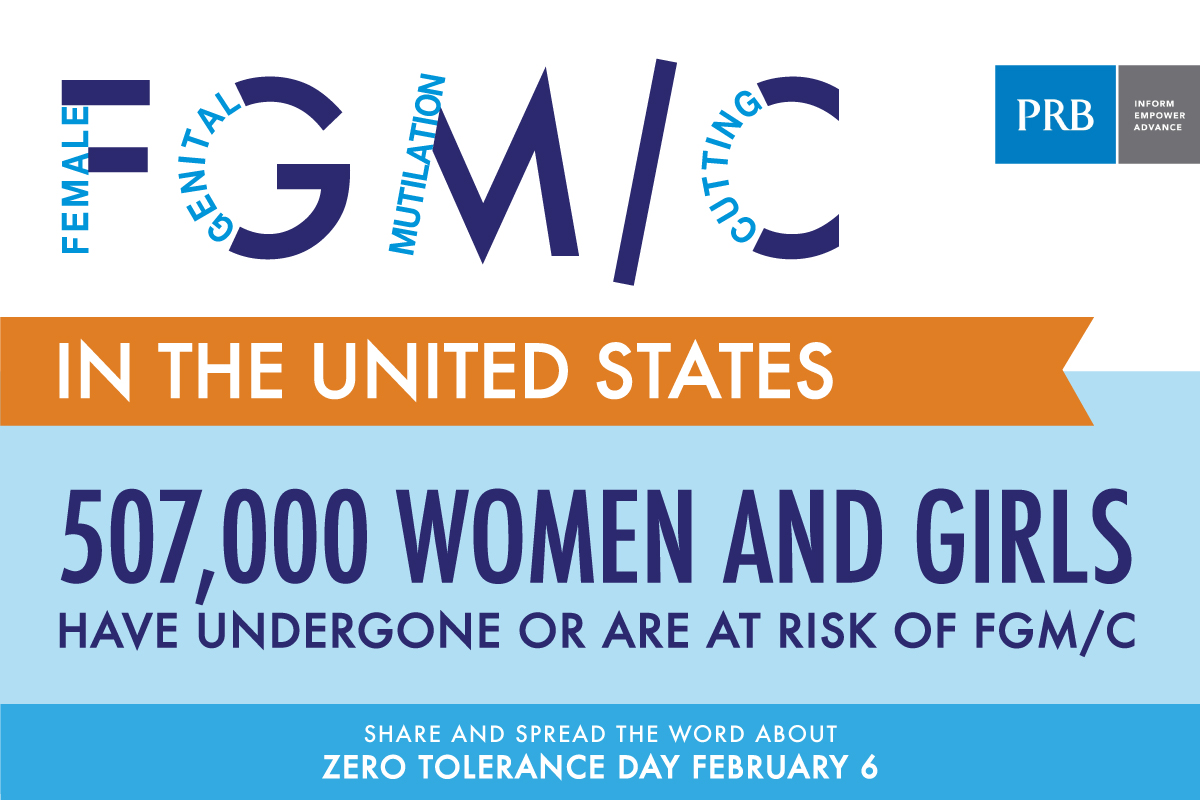

It has been incredibly easy, even comforting, to vilify Dr. Jumana Nagarwala for performing khatna in the US. But let us not buy into the clash-of-civilizations narrative. Each time a US news outlet says the practice will not be “tolerated in the US,” there is an implied comparison to those “backward” countries that tacitly endorse it. Additionally, it implies a wounded nationalism, where (White, male) individuals are almost more outraged that it is happening in the United States than that it is happening at all. And so we are forced to view the practice through an imperial lens. We must not let khatna become a political talking point for US politicians to show how they have “zero tolerance” for “brutal” practices while forwarding a facile concern for women’s rights. We must not forget that khatna is endorsed by the largely male leadership of the Bohra jamaat. While Dr. Nagarwala is culpable, and there is no question that she must face legal action, she has been turned into a scapegoat by both US discourse and the Dawoodi Bohra leadership.

This is a brief account of how khatna shapes my personal narrative, but I want to complicate some of the stereotypes that public discourse about khatna is attempting to forward: that it is an Islamic practice (it is not), that it is a result of poor formal education (again, no), or that it is a violent and barbaric practice that consumes the victim – the answer to that is more complicated than a yes or a no, should someone actually care to engage those who have experienced khatna.